The mixing of chemicals has come a long way. Once, the hand mixing of large batches resulted in inconsistent mixes and waste. That was then. This is now: Highly precise, computerized in-line machines make better-quality emulsions, saving money on labor and transport.

A finer emulsion is just part of the picture. Even with a better-quality blend, chemicals often are mixed in large batches, presenting storage, transportation and degradation problems. Water is a large component of many chemical mixtures and emulsions ," as much as 90 percent in most cases ," so plants must devote considerable space and resources to storage. It also costs more to transport these highly diluted chemicals. Some plants do not have the capability to create these finishes on-site. Finally, large quantities of stored chemicals are subject to degradation and bacteria growth. Such large inventories often contribute to waste.

The textile industry began using technologies such as static (motionless) mixing and in-line (continuous blend) mixing to address these challenges and now is beginning to reap the rewards from the investments. The lessons learned in textiles can be applied to many chemical processing industries.

No moving parts

The first static mixers were developed in the 1960s. A static mixer has no moving parts and works extremely well in creating emulsions ," stable suspensions of one liquid in a second immiscible liquid. Static mixers create stable emulsions because they reduce the particles to a smaller size so they stay together in a stronger bond for a longer period of time.

Emulsion creation is critical to numerous chemical processes. In textiles, emulsions are crucial to finishes ," chemical treatments applied to a yarn or fabric to produce a desired effect. For example, chemical finishes can make towels softer, slacks stain-resistant and blue jeans a deeper blue.

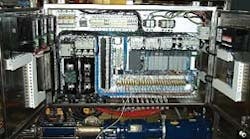

The diagram illustrates the setup of a typical in-line mixing system.

In general, static mixers work by dividing streams of ingredients that need to be mixed. The ingredient stream typically is forced through the static mixer by a pump. The ingredients then are split into substreams as they are forced through the mixer. These substreams then are recombined and divided once again. This process might be repeated numerous times.

The standard static mixer uses baffles to divide ingredients into two streams, but some static mixing designs today divide ingredients into four streams, creating a more homogenous mix. For example, if a stream of water and a stream of chemical agent "A" were pumped into the static mixer, the stream of water and the stream of agent A each would be divided into four streams. These four streams would be recombined and forced through the static mixer again. The four streams would be divided into 16 streams, and so on.

Mathematically, the equation is: N = 4n, where 4 is the number of splits in the stream, and "n" is the number of elements being mixed. As each ingredient is pumped through the static mixer, pressure is applied to keep the particle streams moving at a high rate of speed. Once the particles reach a critical Reynold's number, the common measure of turbulence, they begin to intermingle and form a uniform, consistent mix.

The smaller particles then impinge against one another according to Newton's Second Law: The acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force acting on it and is inversely proportional to its mass; the direction of the acceleration is in the direction of the applied net force. This "Newtonian movement" keeps the ingredients in suspension much longer.

Continuous blend

Continuous just-in-time blending came into its own in the 1990s when static mixing was incorporated into an automated system.

To create an automated continuous mix system, the following components generally are needed: an automated pump system, flowmeters to measure chemical delivery and some type of intensive mixing. Because they are being retrofitted into existing processes, in-line mixers often have to be "back integrated" to satisfy the particular needs of a given process. The components are selected based on the volume requirements and the type and number of chemicals that have to go through them. In-line mixers can be retrofitted into a production line economically and have a footprint no larger than a typical office desk or even smaller.

The components

The major components of a static in-line mixer used in the textile industry ," and potentially in the chemical industries ," include:

Progressive cavity pumps.

Mass flowmeters.

Static mixers.

In-line heaters.

Programmable logic controllers (PLCs).

Progressive cavity pumps move the materials through the mixing process. The pumps provide the mixer with a metered, uniform flow. Typically one pump is used for each product in the mixture. The pumps are extremely versatile, capable of handling materials ranging from abrasives to clear fluids. Each progressive cavity pump can handle liquids with a viscosity as great as approximately 100,000 centipoise.

Mass flowmeters control the amount of each product pumped into the mixture. These devices provide feedback to the pumps to ensure accurate delivery. Users simply enter the proportions of each component into the computer, and the control loop ensures each mix is delivered accurately. The flowmeters also provide on-line measurement of density and temperature.

Traditional mixing devices used in the textile industry had a mixing accuracy range of error between +1 and -1 percent. With a static in-line mixing machine, this accuracy is significantly greater ," the range of error is between +0.1 percent and -0.1 percent.

The static mixer provides the machine with its uniqueness. It allows users to create more than a million mixes in a standard 10-element mixer, and it is applicable for a wide viscosity range.

Another optional feature of the in-line mixing system is an in-line heater. In most textile machines, this heater has a capacity of 4.5 kilowatts (kW) to 1.8 kW and a volume of 2 liters (l) to 3 l. The contact parts typically are Inconnel high-nickel stainless steel or glass, which do not react unfavorably with the chemical mix.

The PLC is the brain of the static in-line mixer. It controls the machine and provides and stores important process information such as amount produced, time of makeup or destination.

The PLC panel of an in-line mixing machine is its "brain."

The benefits

Realize just-in-time mixing.

Use more high-performance products.

Increase accuracy.

Save on labor and transport expenditures.

Gain remote access.

Customize applications.

The most important benefit of the in-line mixer is that it allows users to mix chemicals just in time. Traditional mixers usually make large batches of each emulsion. Often, these emulsions sit in storage awaiting use. Bacteria growth can taint the emulsions, ruining them.

Just-in-time mixing allows users to make smaller amounts of each emulsion and use the chemical compounds as they are needed. Because the smaller batch uses a lesser quantity of chemical compounds, users can afford to purchase higher-quality chemical compounds.

Another benefit of in-line mixing is accuracy. PLCs and mass flowmeters ensure the mixer produces the exact same emulsion every time. Users of in-line mixers can be confident they will produce a consistent and high-quality product.

The automated in-line mixing system and just-in-time mixing reduce labor requirements and transportation costs. Because in-line mixers allow products to be made on-site, users do not have to rely on other companies to mix and then ship large highly diluted batches of chemicals. Instead, they can purchase the concentrated chemicals and make the dilution on-site. As a result, companies that use in-line mixers quickly recoup the initial investment in the machinery through cost savings.

In-line mixing also offers the opportunity for remote control. The automated system can be connected to a centralized control center or accessed by modem. Remote capabilities allow users to monitor the mixer's operation from anywhere with phone access, whether the mixer is in the same building or on the opposite side of the globe. Users also can choose to outsource monitoring to the chemical provider or to control it internally. In addition, basic troubleshooting and repairs can be controlled from afar.

One of the in-line mixer's advantages is its small footprint.

The future

Static in-line mixers offer numerous benefits not only to the textile industry, but also to other industries. As static in-line mixing technology advances, its benefits will become more important. Furthermore, static in-line mixing is adaptable to changing user needs and technologies.

This technology has clear applications in segments of the chemical industry, including synthetic lubricants, agricultural chemicals and adhesives. The mixing process in these industries can be similar to the ones used in textiles ," the chemical ingredients account for the only change. As improvements are made in the in-line mixing process, the static in-line mixer eventually will be able to handle small solid particles such as powders, flakes and pellets.

Further improvements in in-line mixing machines will be process-specific, and each machine will be engineered specifically to meet the needs of the industry and user.

Anderson is a mechanical engineer and is chemical systems manager for Cognis Corp.'s textiles division in Charlotte, N.C. He developed a static-inline mixer and has a number of patents related to plastics and textiles and plastics. Contact him at (704) 945-8830.