During an operation to return a filter back to service, a hydrocarbon spill resulted in a reportable quantity release and an API RP-754 Tier 1 process safety incident. The investigation found that the operator neglected to close the downstream bleed valve, causing the release. Corrective action included disciplining the operator.

Does this scenario sound familiar? It likely will. Industry data indicate that greater than 20% of loss of primary containment (LOPC) incidents stem from a few causes: valves left open, open-ended lines on energized pipe and vessels, and line-up errors. More than 10% of these events occur during equipment startup [1].

Blaming an operator when line-up errors occur seems easy but doesn’t address the underlying problem. We never will eliminate these human-error causes of process safety incidents until we go beyond simply noting “operator left valve open” and answer the question “Why did the operator leave the valve open?”

[javascriptSnippet ]

Analysis of process safety incident data at Celanese indicated that almost half of the incident causes related to conduct of operations — i.e., the management systems in place to ensure operators perform their tasks correctly [2]; a majority of these were line-up errors. The most common operating mode during the incidents is startup or returning equipment to service following maintenance. Recognizing that the most fundamental task operators perform is to line-up equipment, Celanese developed the “Walk the Line” program. It is based on a belief that the operators must know with 100% certainty where energy will flow each time a change is made in the processing unit. The premise of the program is that we can change behavior by providing a culture of setting the expectation for accuracy in line-up, and giving operators the tools to ensure accuracy in line-up.

An Essential First Step

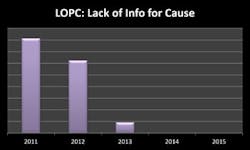

A pre-condition for Walk the Line is understanding the causes of operator line-up error. This becomes problematic if investigations stop at “operator left valve open” as the cause. As Celanese developed our Walk the Line program, it became clear that we first must improve the quality of our incident investigation process and root cause analysis (RCA). We approached this in two ways. After identifying the line-up error incidents, we asked each site to analyze its near-miss and incident data to the best of its ability to identify why the errors occurred. In addition to this analysis, we completed a global incident investigation management-training program that targeted improving the quality of the application of RCA methodology to give greater consideration to human factor causes. We instituted a practice of reviewing all Tier 1 and Tier 2 RCAs to normalize the quality of cause maps and corrective actions. The metric we chose to measure effectiveness of the training and RCA reviews is “lack of information for cause.” Figure 1 shows the improvement trend since these practices were initiated, with 2011 as the base comparison year.

Figure 1. The number of incidents without adequate root cause analysis has dropped dramatically.

As our RCAs improved, we were able to characterize the causes of line-up errors as: expectation for energy control not set, lack of continuity of operations, and deficiencies with operational readiness. Walk the Line was adopted as a readily recognizable way to raise awareness in these three areas.

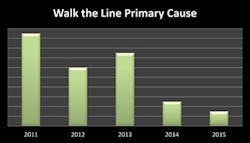

Celanese implemented Walk the Line in 2013 and achieved immediate results. Since implementation, LOPC incidents related to operator line-up have fallen 30% per year on average. Figure 2 illustrates these results. The fact some incident causes persist highlights it may take up to five years to effectively ingrain a practice into the culture for lasting change.

Tailored Implementation

On reviewing the causal data, it was apparent that each site had unique gaps falling within the three categories. The approach therefore was to focus on culture change at the corporate level, provide the operational discipline tools to address operational continuity, and the operational readiness tools to address the mode of operation where these incidents occur. Sites then implemented the program using the tools applicable to their needs.

Culture. The first group of causes centered on the knowledge of an operator’s responsibility for energy control. In some instances, a site had failed to formally document its expectations for operator line-up. In other cases, operators had received initial training on proper line-up technique but never any reinforcement of the concept; refresher and on-the-job training ignored the topic.

Figure 2. Walk the Line has significantly cut the number of events caused by line-up errors.

One way to change this culture is to apply the proper initial training and then follow-up with frequent reinforcement of the expectation that operators must know with 100% certainty where energy will flow each time they make a change to the process. From a corporate perspective, we produced and distributed a number of tools designed to raise the awareness of this expectation. These include:

1. Two-day regional workshop meetings with front-line supervisors that reinforce conduct of operation tools for continuity of operations and operational readiness.

2. Periodic newsletters distributed in native languages across the globe describing Walk the Line expectations and tools.

3. Toolbox presentations of actual incidents caused by line-up errors. These presentations aim to enable front-line supervisors to open dialogs with operators on “what would you do” to prevent the incident. (For details on novel, just-launched interactive safety training tools, see “Achieve Better Safety Training.”)

4. Standard Walk the Line training packages that can be used as is or modified for a site’s individual needs.

5. Short corporate videos that, as part of our process safety lessons learned program, help reinforce the message of Walk the Line.

After three years of raising awareness and setting the expectation, we continue to use terms such as “Walk the Line incident” when describing line-up errors to remind the organization of expectation for energy control.

In 2015, the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM) launched Walk the Line in partnership with member companies as part of the AFPM and American Petroleum Institute (API) Advancing Process Safety Program. Walk the Line is a practices-sharing program designed to help prevent operator line-up errors that cause approximately 20% of all process safety events (according to industry data [1]). This program is successfully raising awareness of operator line-up errors and providing simple solutions to prevent these types of mistakes in the future. Walk the Line materials include “what/if” scenarios, training, conduct of operation practices, operational discipline practices, and operational readiness practices.

For more information, contact AFPM at [email protected].

Continuity of Operation and Operational Discipline. In the early phases of Walk the Line, the most common question from operators was “Do we have to physically walk the line each time we make a change?” The answer is, if you don’t know with 100% certainty where the material will flow, then yes. However, several tools can help operators grasp the present operating state of a processing unit. Understanding the current line-up and changes to the line-up is one aspect of continuity of operations. The tools are called operational discipline tools because they introduce a discipline to operations that encourages repeatability in results [2].

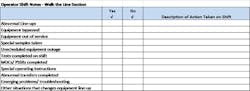

The operational discipline tools used include: shift instructions, shift notes, expectations of shift relief, shift meetings, and operator evaluation sheets with both informal and formal rounds. Each incorporates the Walk the Line theme through a dedicated section that describes in checklist format common and uncommon situations that give rise to changes in the unit that might lead to a line-up error. Shift supervisors have an opportunity to reinforce the expectation for Walk the Line when they write shift instructions. Highlighting potential line-up issues when discussing the current jobs on shift at the toolbox or shift meeting provides another opportunity. Operators can communicate the changes made on shift by citing them in shift notes, and using these shift notes during shift relief. Each site is expected to define an informal and formal evaluation route and train operators on what to look for during the equipment evaluation. In addition, evaluation round sheets should include location of critical bleeders, valve positions and other critical line-ups so that operators check them each time they make their rounds.

As noted, these tools share a common element — a pre-defined Walk the Line checklist. It must be completed and communicated, regardless of whether a change has been made. This repetition helps build the culture of Walk the Line. Figure 3 shows an example checklist for operator shift notes used during shift relief. This checklist identifies those activities that lead to changes in line-up. These changes are communicated between and among shifts, with confirmation of review required. Operators returning to duty must give positive verification since the last review.

Another class of aids to help operators understand the current operating state of a unit involves design tools. For example, a process to identify critical bleeders will highlight those points in the process that must have a bleed valve shut with a plug to prevent an LOPC incident. At Celanese, some sites paint these critical bleeders a recognizable color (Figure 4) and have the operator inspect them during evaluation rounds.

Additional design practices, to name a few, include formal plug and inspection programs, line labeling initiatives, spring loaded valves, and double blocks on some bleeders.

Operational Readiness. Experience has taught us that the frequency of incidents is higher during process transitions such as startups. These incidents often result from the physical process conditions not exactly matching those intended for safe operation. Thus, it is important that the process status be verified as safe to start. Operational readiness reviews ensure the process is safe to start by examining issues such as:

Figure 3. This short checklist is used for operator shift notes and shift relief.

• equipment line-up;

• safeguard bypasses restored;

• bleed valves plugged;

• leak tightness;

• pre-startup safety reviews completed; and

• car seals in place.

Such reviews of simple startups may involve only one person walking through the process with a straightforward checklist to verify that nothing has changed and equipment is ready to resume operation. More complex reviews or higher risk startup situations may require different tools.

Operational readiness tools share some common elements such as defining equipment commissioning steps in standard operating procedures (SOPs). Commissioning tools include: process and instrumentation drawings (P&IDs) walk-downs, formal pre-startup safety reviews (regardless of whether a change was made), soap testing, checklist SOPs and similar maintenance/operations turnover, and verification after maintenance checks designed to ensure bleeders are closed and line-ups are correct.

A common tool used in industry is independent verification. It often targets some safety devices such as pressure relief devices but also makes sense for critical line-ups. Celanese uses a risk-based ranking criteria to determine if a task should be considered critical. These tasks are performed with a checklist in hand; the operator verifies each step when completed. After the task is finished, another person independently confirms the steps as complete and accurate.

Figure 4. Bright yellow color alerts staff to importance of this bleed valve.

Step Up Your Efforts

Adopt a belief that all process safety incidents are preventable and start with a goal of zero LOPCs caused by operator line-up errors. Of all LOPC incidents, those related to incorrect line-ups and open ends seem easiest to correct. When analyzing incidents, go beyond “operator left valve open” and answer “Why did the operator leave the valve open?”

Recognize which operating discipline and operational readiness tools operators require to understand the current operating state of the processing unit. Set the expectation that an operator must know with 100% certainty where energy will flow each time a change is made to the process. If that person doesn’t know with 100% certainty, then walk the line!

JERRY J. FOREST is global process safety manager for Celanese, Irving, Texas. E-mail him at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. AFPM Safety Portal Event Sharing Database, www.afpm.org/safetyportal (login credentials required), American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers, Washington, D.C.

2. AIChE Center for Chemical Process Safety, “Conduct of Operations and Operational Discipline,” J. Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, N.J. (2011).