Safety: Boost Your Plant’s Profitability

Controlling safety is of upmost importance in chemical manufacturing operations. Unfortunately, most chemical companies handle safety — primarily occupational safety, e.g., trips, slips and falls — as an adjunct to the business unit, not as a mainstream business operation. Typically, an environmental, health and safety organization manages safety across a company’s business units. Although this approach has worked well for the most part, making both process and occupational safety an integral aspect of every business unit should be the ultimate vision for industrial operations. Tying safety directly to the profitability of an operation can play a key role.

Traditionally, chemical makers relied on monthly data provided by their business reporting systems to manage the profitability of operations. However, over the past decade, some critical business variables that influence profitability have started to fluctuate more frequently than monthly. For example, the prices of electricity and natural gas on the open grids in the United States can change every 15 minutes. This, in turn, impacts the price of raw materials and products. Onsite storage of materials and products has tended to hide the effect of this real-time business variability at the operational level, often at the expense of a higher-than-desired expenditure of working capital.

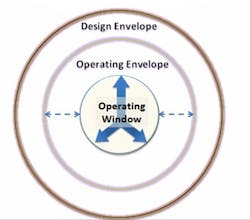

Figure 1. This simplified model shows how safety constrains profitability.

The good news is that not all business variables associated with the profitability of an operation are experiencing real-time variation. In fact, in most operations only three critical business variables have tended toward real-time variation: energy costs, material costs and production value, i.e., the value of products being made. The primary objective of most chemical operations is to maximize production value while minimizing energy and material costs. In most cases, though, safety of the plant, personnel and the environment constrain the balancing of these three critical real-time business variables to maximize profitability. Figure 1 illustrates a simplified model of this relationship and underscores the direct linkage between profitability and safety.DESIGN AND OPERATING ENVELOPESChemical processes are designed to operate within certain limits intended to enable both safe and profitable performance. These design limits determine the process equipment selected. Pushing the operation beyond these limits will exceed the design constraints of the operation and likely may result in an unsafe event occurring. The operational domain within the design limits can be thought of as the design envelope. It represents the operating limits at which the probability of an unsafe event approaches 1.0.For safety reasons, chemical plants seldom, if ever, are pushed close to the design constraints. The operations and engineering teams must evaluate the safety risk of the operation and set a reasonable operating limit based on the probability an unsafe event will occur if operating at that limit for a given period of time. That probability is referred to as the safety risk of the operation. Whenever the plant is operating, there’s some degree of safety risk. Obviously, the objective is to avoid unsafe events to the highest degree possible while still running the facility in a profitable manner. Plants implement functional safety systems, e.g., emergency shutdown, fire and gas protection, to minimize the negative consequences of an unexpected process excursion or external event. These systems are reactive in nature and will shut down a process area or entire plant if unsafe operating conditions are detected. Such shutdowns prevent damage to people, the environment or equipment but at the cost of lost revenue.Figure 2. The operating window ideally should come close to the boundary of the operating envelope.

Figure 3. Combining simple measures of operational and conditional safety risk provides an overall measure of safety risk.

Figure 4. Real-time measurement of safety risk provides an important tool for maximizing profitability.

PETER G. MARTIN, PhD, is Foxboro, Mass.-based vice president of business value consulting for Schneider Electric. MARTIN A. TURK, PhD, is Houston-based global director, hydrocarbon processing industries for Schneider Electric. E-mail them at [email protected] and [email protected].