Heating Promises Better Bioplastics

Conventionally prepared bioplastic fibers are known for their lackluster resistance to heat and moisture. In addition, producing the material on a commercial scale usually involves solvents and other expensive, time-consuming techniques. Adding a simple step — raising the temperature of bioplastic fibers — resolves these issues, and could allow manufacturers to continuously produce the biodegradable material on a scale that at least approaches petroleum-based plastic, say researchers from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Neb., and Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China.

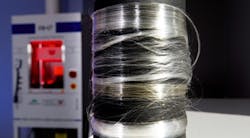

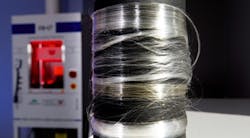

Figure 1. Nebraska researchers collaborated with colleagues in China to develop a more robust, biodegradable plastic fiber derived from corn starch. Source: University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

The approach works with polylactic acid (PLA), or polylactide, a component of biodegradable plastic that can be fermented from corn starch, sugarcane and other plants. However, the material’s sensitivity to water and heat limits its industrial use. The team knew that stereo-complexation of PLA molecules, i.e., creating a combination of “L” and “D” enantiomers, typically results in a more robust material than one with just the L or D version. However, this process required costly and harmful solvents and agents. So, the researchers took a new approach. After mixing pellets of the L and D polylactide and spinning them into fibers, the team rapidly heated them to as hot as 400°F.

Compared to plastics containing only the L or D enantiomers, the heat-treated bioplastic resisted melting at more than 100° higher. It also maintained its structural integrity and tensile strength after being submersed in water at more than 250°. An article in Chemical Engineering Journal provides more details on the process.

“This clean technology makes possible (the) industrial-scale production of commercializable bio-based plastics,” say the researchers.

A feasible green alternative to petroleum-based manufacturing could pay off both environmentally and financially, believes Nebraska’s Yiqi Yang, who led the research. “So we just used a cheap way that can be applied continuously, which is a big part of the equation,” he notes. “You have to be able to do it continuously in order to have large-scale production. Those are important factors.”

The team has demonstrated continuous production on a small scale and will next ramp up to further illustrate how the approach might be integrated into existing industrial processes. The approach could be readily incorporated into current continuous industrial-scale production lines, notes Yang. This would involve normal melting, spinning and other fiber/textile facility processes, he says.

Usually, an improvement in one property involves a tradeoff in another property. Yang admits, “We have not studied the degradability of the products yet, but it certainly will slow the degradability of the products,” he believes.

Once pilot-scale production begins, Yang expects some challenges might surface, in particular, optimizing conditions. “We will need industrial partners to have pilot-scale production. Hopefully, in the next two-to-three years,” says Yang.