“The future only looks bright for wireless,” says Rob Brooks, process control supervisor at PPG Industries, Lake Charles, La. “Wireless lets you put information into operators’ hands that was not possible before. Wireless is a boon to safety, as well as operat-ing and maintenance procedures.” Brooks’ upbeat assessment is shared by many.

Implementation of wireless technology in the chemical indus-try remains spotty, but that will change if a July 2005 Chemical Processing poll is any indication. In it, 37% of the respondents said their site’s interest in wireless was very high; 18% said high; and 15% said moderate.

“People are just experimenting with wireless point solu-tions,” remarks Hesh Kagan, president of the Wireless Industrial Networking Alliance (WINA) and director of technology for new business development for Invensys Process Systems, Foxboro, Mass.

“Most installations we’ve seen are where companies are try-ing to prove to themselves that wireless works in their environ-ment,” notes Steven Walker, engineering manager for Adalet Wireless, Cleveland.

Substantial savings

The main draw is economics, says an instrument control specialist at one multinational company’s plant. “If you can put in wireless, you avoid the costs of wire, conduit and cable trays.”

Energy savings are another strong incentive, says Jeff Yel-lets, senior segment marketing manager for Honeywell Process So-lutions, Phoenix. He notes, for instance, that steam-trap monitoring is the focus of a lot of current wireless activity.

Ten percent of the energy consumed in industries such as pet-rochemicals, steel, paper and glass could be saved by going to wireless, says Wayne Manges, wireless program manager at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tenn.

Proponents say that wireless technology promises to do more than save money — it will revolutionize plant operations.

Broadening use

Right now, wireless gets the nod mostly for non-critical duties like level monitoring, especially at remote and off-site locations. How-ever, companies today are trying wireless for more than simple monitoring functions, notes Dave Kaufmann, director of business development for Honeywell. Some are starting to opt for wireless for keeping tabs on the custody transfer of raw materials across fence lines and even for critical services such as process control and safety. For instance, Yellets points out that plants are using wireless acoustic sensors downstream of relief valves and rupture disks. Kaufmann adds, “I was amazed at a customer using wireless for safety. They did all the necessary risk assessments. Wireless was best for them, they said.”

The biggest applications remain tank level monitoring and communications between field devices, says Jake Millette, senior analyst with Venture Development Corporation, Natick, Mass. One appeal of wireless is that it can serve as a gateway, or relay, be-tween two different vendors’ systems, such as a Siemens device and an Allen-Bradley controller, he notes.

Wireless input/output is hot in traditional systems, says Gra-ham Moss, president and founder of Elpro Technologies, Stafford, Australia. “We have customers that are buying programmable logic controllers (PLCs) purely as data-acquisition systems and then connecting the PLCs to wireless modems.”

Real-world examples bear out these observations.

For instance, since 2002, CDR Pigments & Dispersions, Hol-land, Mich., has used three Elpro transceivers at its wastewater treatment plant. Maintenance coordinator Mark Nyboer notes the units transmit data on pH, dissolved oxygen, flow, temperature and control valve position from the wastewater treatment basin to the main building. Previously, CDR sent the data by overhead cables. But lightning storms regularly disabled wired transmitters. “We discussed putting the wires underground, [but] it was cheaper to do wireless,” he adds, noting CDR saved $4,000 to $5,000.

Denver-based Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. just installed Emerson Process Management’s wireless equipment at its 20-million-ft3/d natural-gas compres-sor station in Parachute, Colo. It uses a level transmitter on each of three storage tanks that contain an oil/water mixture created from condensate, as well as a differential-pressure transmitter and one temperature transmitter at the glycol contactor. Encana has already seen cost savings, says Brandon Robinson, instrument-and-electrical (I&E) technician.

At its nylon 6 plant in Freeport, Texas, BASF uses approxi-mately 70 transmitters from Accutech Instruments, a division of Hudson, Mass.-based Adaptive Instruments. The transmitters pro-vide data on the positions of various isolation valves to a ModBus master, says Tom Kleiner, senior I&E engineer. The master inter-prets data and then activates lights on what’s called a mimic panel used by operators. “Wireless saved us from running wire for both power and signal to the valves,” he says, estimating a savings of $50,000.

BP is investigating the use of six Adalet wireless temperature transmitters on a paraxylene crystallizer. “We’ve been looking for this technology for years. It’s for use in hazardous locations,” ex-plains research engineer Ronald Stefanski, based in Naperville, Ill. He believes that commercial use of the technology at a plant in the U.S. (Figure 1) will be the worldwide paraxylene business unit’s first application of wireless. “We’re excited about the potential.”

Figure 1. A plant such as this one in Decatur, Ala., may inaugurate worldwide business unit’s use of wireless in a hazardous location.

Emerging standards

To integrate different manufacturers’ wireless devices, users want to standardize on a single wireless “cloud” — an umbrella or network — over their plants, Kaufmann says. “What we’re hearing in the SP100 area [in ISA’s SP100 Committee, Wireless Systems for Automation] is that some end-users say they’re looking to put 20,000 wireless sensors at an installation.” He explains that SP100 is developing a user-driven, protocol-neutral standard.

But the product of the SP100 Committee will be a best prac-tices, not a technical, standard, says Gabe Sierra, Chanhassen, Minn.-based wireless marketing manager for Emerson Process Management. Meanwhile, the Wireless HART Working Group of the HART Communication Foundation, Austin, Texas, is develop-ing a standard — self-organizing networks — that will be the de facto standard for in-dustry moving forward, he says.

These self-organizing networks will totally revolutionize what plant operators can do, Sierra asserts. “It’s going to allow them to monitor assets they couldn’t before,” he believes. “They’ll be able to collect more field data and be able to implement new maintenance operations that will help them extend the life of the plant, as well as increase plant productivity.”

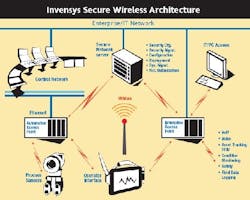

Seeking its own wireless cloud right now is PPG Industries’ complex in Lake Charles, La. The 700-plus acre facility, which manufactures chlorine, caustic and other chemicals, ventured into wireless just last year, notes Brooks. Now it has 40 to 50 devices that measure temperatures, pressures and tank levels. “I’m looking for a common security model and a common administration model,” Brooks says. Invensys Process Solutions currently is working with PPG to build those and is using shared-access-point technology for all devices and a common data-and-security model for all wireless frequencies and protocols (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Shared access points and common data and security model are key to architecture (click to enlarge).

Meshing devices

Those standards and managed networks will foster change, espe-cially in connectivity. And mesh networks, which rely on a lattice-like rather than point-to-point configuration, will revolutionize ex-isting wired linkages, Yellets predicts.

These mesh networks allow sensors to communicate with each other rather than through a base radio, Millette explains. This means, Moss notes, that a wireless device does not need to be able to transmit over as long a distance.

“Give it maybe three years, possibly more, I think mesh will be there in one shape or another,” Moss believes. Yellets is even more optimistic, “As mesh networks come out, in the next year to 18 months, we’ll see the change.”

Mesh networking creates possibilities for more wireless de-vices — not just process devices, but mobile operator stations, hand-helds for field operators’ rounds, and units for safety and maintenance inspections, Yellets contends.

Another significant change will come by coupling wireless technology with tablet personal computers (PCs), such as those of-fered by Honeywell and Invensys Wonderware, Lake Forest, Calif. This will enable plants to rethink what they can do in unwired re-mote areas. It could also be useful outdoors for supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) applications, notes Ann Ke, Won-derware’s product-marketing manager for panels and tablets.

As part of its plan to install wireless Ethernet for control, the multinational company plant cited earlier plans to use tablet PCs to replace 10 fixed operator displays that have human-machine-interface software. “If the tablet PC works like we hope, there are other applications where we could use it,” the site’s instrument control specialist says. He estimates potential savings at approxi-mately $40,000.

Healthly change

Wireless promises other significant changes in industry practices. The biggest one will be an increase in condition monitoring, say Hagan and Manges, who is also a WINA board member and co-chair of ISA’s SP100 Committee

Eliminating the need for wiring makes it easier for plants to get data from units that otherwise would be tough or expensive to check — and is already prompting more monitoring of the condition of equipment such as pumps and mo-tors, which, in turn, ultimately leads to maintenance savings.

Adding to the incentive, a new class of low-cost wireless sen-sors will compel companies to use those sensors with equipment, Kagan believes. These sensors — for tem-perature, pressure, vibration, level and flow — don’t have the same resolution as process sensors, Kagan explains. But, he emphasizes, “There’s a lot of science, math and common sense that tells you that a lot of casual measurements might be more useful than a few exact measurements.”

The chemical industry, like others, will see sensors with built-in wireless technology, predicts Harry Forbes, senior analyst at ARC Advisory Group, Dedham, Mass. He also forecasts big in-roads in the next two to three years for wireless sensor networks, because they boast lower installation costs than wired ones.

Key applications will be monitoring, process control and as-set management — and within those will be both critical and non-critical uses, Kaufmann says. The two top barriers to adoption, though, are reliability and security, he con-tends. Power management also concerns end-users, he and Forbes say. Kaufmann notes that users want plug-and-play-and-walk-away sensors with batteries lasting 15 years.

Wireless’ tangles

Wireless is not without its issues, however. Foremost among these are coexistence and interoperability with other wired and wireless networks, the need for standards, and lack of infrastructure.

“People are coming in and implementing their own point-to-point solutions. Invariably, when they do the first solution, it works. Even the second might work,” Kagan explains. “But this is wireless we’re talking about — radio waves go wherever they want.”

Plant processes may stop working because of these ad hoc networks, Kagan asserts. “In ad hoc, there’s no engineering. It’s just who gets there first. In wireless, there must be thoughtful, top-down engineering.”

The problem is exacerbated because there are only two fre-quency bands — 900 megahertz and 2.4 gi-gahertz — that are open for public use. “These are like multi-lane, public highways that anyone who wants to build on can,” Kaufmann explains. But without rules, traffic gets jammed, he says. “We’re headed for a big crash in the future. I don’t know if everyone in the plant [with a lot of wireless imple-mentations] recognizes that.”

Users need coherent systems management through a common data model, Kagan adds, because people don’t know how to man-age wireless technology. A solution will come from ISA’s SP100 Committee, he believes.

An inevitable force

Despite the current drawbacks, wireless technology seems destined to become ubiquitous at plants. The cost and complexity of wired systems will drive plants to wireless, believes Manges.

Yellets foresees more wireless with redundancy and new plants designs with wireless. “We’re going to see that for all read-ings, including critical process readings,” he says. Among those critical readings, he includes key reactor temperatures and pres-sures that may require very fast response time to control.

Kagan says there’s a huge difference between what’s happen-ing today in wireless and what will happen tomorrow. Though cer-tain that the technologies can be implemented correctly, he cau-tions, “It’s not a trivial task. It’s more expensive than managing a wired network.” But whatever the costs, benefits of correct wire-less implementations are enormous, he believes.

One clear beneficiary is a company’s bottom line, Brooks says. “We [at PPG] see that in order to be competitive, this is step we felt we need to take.” More and more chemical companies are coming to the same conclusion.