Rice University Secures $4 Million for Materials Research

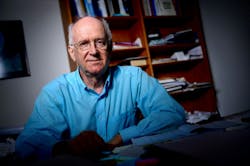

Rice University materials scientist and professor of engineering Boris Yakobson received three awards from the U.S. Department of Energy and the Department of Defense for $4.1 million to research challenging aspects of advanced materials’ production, performance and dynamics, according to a university public affairs office article.

The research team is working on a project called “Mapping the synthetic routes for 2-dimensional materials.” The goal is to understand molecular mechanisms that enable 2D materials production for electronics applications, including microchips.

Building on previous work on several 2D materials, such as graphene, molybdenum disulfide and hexagonal boron nitride, the researchers hope to establish a general approach to developing predictive synthesis models for perovskites, nitrides, oxides and other materials used in energy and electronics applications.

“We also aim to automate the search for reaction paths that would allow us to synthesize new, previously unknown materials or to simplify the production of materials like borophene, which now require expensive or esoteric techniques,” said Yakobson, whose proposed work on 2D materials will be supported by $2.1 million over several years from the U.S. Department of Energy.

The Yakobson Group also received a combined $2.03 million over the next four years from the U.S. Department of Defense for two projects — one looking at interfaces in composite materials and another on the behavior of energetic materials in extreme nonequilibrium states.

“One of these projects looks at the atom- or molecular-level details of how interfaces — the borderlines between microcomponents in a mixed solid — respond to extreme load,” Yakobson said.

Interfaces impact the overall performance of composite materials, and properties such as mechanical strength, toughness, electrical resistivity and thermal and corrosion stability are of critical importance in both civil and defense infrastructure and applications from bridges and railroads to submarines and supersonic aerospace vehicles

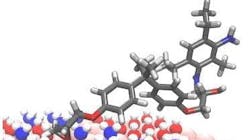

“Electronic glue” holds the atomic lattice of a ceramic material exposed to extreme heat and radiation, when the constituent ions change their charges and mobility. (Graphic courtesy of the Yakobson Research Group/Rice University)

The second DOD-sponsored project will focus on developing ways to quantify the rates of chemical reactions and other processes that occur in complex systems in states far from chemical equilibrium.

“Systems that are far from thermodynamic equilibrium will exhibit significant spatial variations or gradients in terms of energy density, chemical composition and more, making it difficult to determine the speeds of processes,” Yakobson said. “This is very important to know, especially for energetic materials, which are a broad class of materials that store a large amount of chemical energy.”

Examples of energetic materials include explosives, fuels and propellants. Drawing on insights from solid state chemistry, Yakobson seeks to “make a dent” in the relative dearth of knowledge on how stress-mediated reactions and the spatial heterogeneity of nonequilibrium systems play out in gas- and liquid-phase processes.