Related Content You May Enjoy. . .

Avoid Blending Blunders

Get a Handle on Solids’ Flow

Install Pneumatic Conveyors Correctly

Prevent Fine Powder Flushing

Unlock Better Blending

While no one would deny the challenges involved in processing liquids and gases, powders are in a league of their own. Those charged with the design and operation of fluid processing plants have access to extensive physical property databases and well-established tools for property estimation and process simulation. In contrast, there’s a wide range of possible powder characterization techniques — from simple angle of repose to comprehensive analysis with a universal powder tester — but little published data. The process relevance of what information exists often is far from clear. Powders are complex systems consisting of solids or particulates, a continuous gaseous phase (usually air) and, almost always, a liquid component. Their properties are a function of composition and an array of particle parameters that includes size and distribution, surface roughness and hardness. Vibration, compaction, attrition, segregation and many other factors influence behavior. This makes measuring powders in a reproducible and meaningful way difficult; predicting flow properties from basic parameters, such as particle size, is well beyond current capabilities. So, powder processors have learned to rely on experience rather than fundamental knowledge. They tend to solve problems using a trial-and-error approach — and often can’t pin down the underlying cause or even why a solution works. Such a trial-and-error approach can succeed but is time consuming and expensive. Furthermore, the experience gained, unless it extends underlying knowledge, has limited applicability. Drivers for Process ImprovementAs margins tighten any processing inefficiencies become less and less tolerable — many plants already have solved the easiest problems. Further progress requires manufacturers to develop in-depth understanding to push units to their efficiency limits and maximize return on investment. Typical goals may be: • raising throughput by decreasing downtime or increasing flow rates;• reducing waste by consistently maintaining product specification and cutting rework;• switching to lower cost feeds; and• automating process control. To achieve these targets the manufacturing team must know what changes to make — and understand the impact that any change will have on the process and product. The starting point has to be the existing experience base but this, in its raw state, only can be used to improve operation within a well-mapped window. If aspects of processing experience can be correlated with specific powder properties then a better understanding can be developed. Knowing which variables determine how a powder behaves in a given situation is the first step toward more-effective control. Using such knowledge to extend operation outside the established working envelope is the way to meet more-exacting performance standards. Figure 1. Powder Rheometer: This device can

characterize powders in compacted and other states

that simulate process conditions.

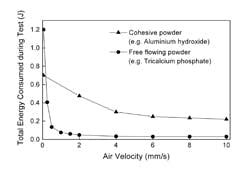

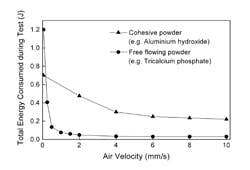

Figure 2. Investigating Aeration: Results of a study of the

effect of air on two powders underscores how differently

powders can behave because of aeration. A small amount

of air can dramatically improve flow properties of some powders.

Click image to enlarge.

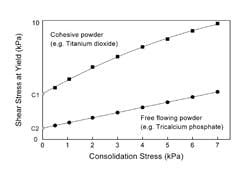

Figure 3. Measuring Shear Properties: When particles flow,

they shear, i.e., slide relative to one another, and this influences

flow characteristics. Powders with greater resistance to flow may

form stable bridges.

Click image to enlarge.

Material |

PR rating |

Problems |

| Formulation 1 | 2 | Potential segregation during transfer |

| Formulation 2 | 5 | Bridging and adhesion to machinery |

| Formulation 3 | 8 | Weight variability and high wastage |

About the Author

Tim Freeman

Freeman Technology

Sign up for our eNewsletters

Get the latest news and updates