Biocatalyst Boasts Benefits

Genetically modified cyanobacteria can produce enzymes providing high selectivity for making chemicals, with the bacteria using photosynthesis to provide the energy needed by the enzymes, report researchers at Ruhr University Bochum, Bochum, Germany. The approach offers simplicity and ease of production of the biocatalyst, and may suit the production of pharmaceutical ingredients and fine chemicals, they contend.

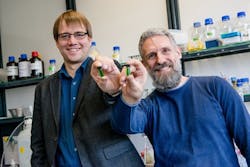

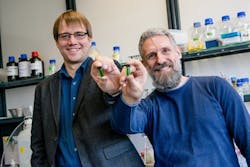

Figure 1. Robert Kourist (left) and Marc Nowaczyk have coupled oxidoreductases with natural photosynthesis. Source: Ruhr University Bochum.

“The enantioselectivity is the reason why we apply enzymes; otherwise, the chemical reaction is cheaper,” notes Robert Kourist of the Junior Research Group for Microbial Biotechnology. “Another advantage of the enzymes is that is quite easy to couple several steps to reaction cascades. Cascades are quite difficult in chemistry since the reaction conditions of the steps differ considerably… Once the molecular biology tools are developed for cyanobacteria, we can aim for light-driven cascade approaches.”

“In principle, the process can be used with all enzymes that receive electrons from NADPH [nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate] or ferredoxin. Other than the similar cofactor NADH, it is not easy to supply NADPH in bacteria or yeast. This is a particular strength of cyanobacteria. I see the greatest potential of the technology for selective oxidation reactions such as oxyfunctionalization,” he adds.

Kourist and Marc Nowaczyk, chair of Plant Biochemistry, (Figure 1) believe the work of their team represents the first example of the use of a cyanobacterial photosystem to fuel biotransformations with recombinant enzymes. The team achieved light-catalyzed highly enantioselective reduction of C=C bonds with Synechocystis cells harboring a NADPH-dependent enoate reductase. Their experiments also showed that enzymes from other organisms can be introduced successfully into cyanobacteria, enabling use of the approach for other reactions. More details appear in a recent article in Angewandte Chemie International.

[javascriptSnippet ]

The proof-of-concept work gave product concentrations and space-time yields too low for industrial processes, the researchers admit, while also stressing that the system remains to be optimized.

“A current bottleneck in comparison to other bacteria is that the need to supply light limits the cell densities. We could work up to 2 g/L, while a typical cell density of E. coli is 40 g/L. This means that cyanobacteria need to be 20 times faster producers than E. coli in order to compete,” says Kourist.

The next steps in the development are increasing the space-time yield because a ten-fold improvement is needed in the scaleup, and investigating other NADPH-dependent oxidoreductases to see about the general applicability of the approach, he notes. This work should take 2–3 years.

“On one hand, we intend to use metabolic engineering to increase the yield of the photosynthetic NADPH-supply; on the other hand, we plan to use process engineering in order to improve the availability of light for the cells, which will allow [us] to increase the cell density,” he explains.

The team hopes to reach 5-L scale within 2–3 years and currently is discussing this with potential partners from industry, Kourist says.