Mechanical Force Triggers Catalyst

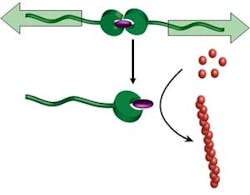

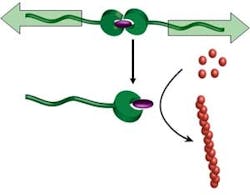

"Let the force be with you" may take on a meaning beyond "Star Wars," due to work at the Department of Chemical Engineering and Chemistry at the Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, the Netherlands. A research team there has discovered a way to activate dormant homogeneous catalysts by exerting force."Latent catalysts that are activated by an external agent (e.g., acid) or by raising the temperature are well known, and they are useful because they provide a method to have the catalyst present in a stable form that can be activated when necessary. The present mode of activation is novel and without precedent, and opens entirely new possibilities in the range of applications, the most important of which I consider its use in self-healing polymeric materials," says Rint Sijbesma, a professor in the department, who worked on the development with Alessio Piermattei and Karthik Sivasubramanian.By incorporating a latent polymerization catalyst in a material, it might be possible to use the mechanical stresses that cause cracks to repair them — by initiating polymerization to reinforce the material at the exact time and place needed, explains Sijbesma.Besides their use for self-healing polymers, reactions that can be switched on by strong shear forces can be extremely useful in reaction injection molding of polymers and in reaction control in lab-on-a-chip applications, he notes.