Successfully Reduce Process Safety Events — Part 2

The first article in this series ("Successfully Reduce Process Safety Events — Part 1") introduced Dow’s program for reducing process safety incidents (PSIs) based on the concepts presented by Vaughen and Klein [1]. It illustrated the idea of leadership at all levels and described two programs associated with our operational discipline systems: cardinal rules and training to maintain corporate memory. Here, we cover three more programs that play an important part in our day-to-day success in preventing incidents; these involve using a process safety focal point (PSFP); recording near-misses; and doing root cause investigation (RCI) and sharing of learnings.

Process Safety Focal Point

Dow has found that designating within an organization a specific PSFP role — tasked with raising awareness of process safety at the facility level — provides a focus to the process safety management systems as well as support necessary to ensure process safety requirements are met. In practice, each operating facility assigns an individual to be PSFP. This person — a senior plant engineer, who assumes the role while retaining current duties — is the key resource on technical issues relating to process safety for the particular production, site logistics or environmental unit. The PSFP works closely with the technology experts to provide proper interpretation and guidance on process safety requirements and practices.

Core responsibilities of the PSFP include:

• performing process safety reviews as part of the management-of-change (MOC) procedure at the facility and calling in experts for further review where required;

• facilitating gap assessments against Dow mandatory requirements and local regulatory standards and working with plant leadership to gain resources to close identified gaps;

• participating in and helping to prepare for RCIs, reactive chemical process hazard analyses and other process safety requirements as necessary;

• maintaining the process safety documentation for the facility;

• working with the maintenance group to review mechanical integrity and instrumented-protective-system test and inspection results and following up as needed;

• assisting in developing plant, business and site process safety goals and assessing progress or defining opportunities to achieve performance goals;

• supporting the development and delivery of process safety training in the facility;

• ensuring the reporting and investigating of process safety near-misses (PSNMs) and process safety and containment events; and

• actively engaging in geographic or business PSFP networks and communication meetings to share best practices and “Learning Experience Reports” (LERs).

Dow has a number of process safety networks for sharing knowledge on technology as well as recent learnings. Business and technology networks include technology center representatives and all the PSFPs for the business globally. Site and geographic networks include local representatives and all the PSFPs from that geography.

The objectives of these networks are to:

• sustain a high level of process safety knowledge within Dow manufacturing by sharing best practices and innovative approaches to managing hazards;

• provide interpretation and guidance on process safety requirements and practices;

• share process safety and containment learnings as well as near-misses to minimize the probability of occurrence; and

• enable a structured approach to developing the knowledge of PSFPs and other network members on the technology of process safety.

Process Safety Near-Misses

Major PSIs in chemical manufacturing are infrequent. However, when they do occur, the consequences can be severe. For example, the Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion and oil spill (Apr. 2010) [2], Imperial Sugar Refinery dust explosion (Oct. 2009) [3] and BP Texas City Refinery vapor cloud explosion (Mar. 2005) [4] significantly impacted human life and the environment and received extensive coverage by the media.

Figure 1. Near-misses can provide key insights for avoiding major incidents.

Corporate performance goals often are measured in such a way that a plant could operate for many years without a major process accident while still not meeting an acceptable level of performance. That’s why paying attention to near-misses — i.e., events in which an accident involving a chemical process was narrowly avoided — is important [5, 6]. PSNM reporting is intended to be a more sensitive indicator of actual performance. The value of such reporting is not in the counting of events but rather in the ability to recognize the potential for an accident, the opportunity to identify and implement corrective actions and the prospect to gain knowledge that may prevent future accidents.

In 2009, Dow began to emphasize PSNM reporting globally as a key leading indicator of performance. The general principles that apply to PSNM reporting are:

• The event must directly involve a chemical or chemical process.

• A failure must occur.

• There is a learning value (taking into consideration both the actual and potential severity of the event).

Facilities report and investigate PSNM incidents to discover and eliminate their potential causes. Dow considers a high number of PSNMs reported as a positive indicator — because we believe that investigating and eradicating the sources of near-misses also will remove the underlying causes of potential incidents before they happen.

Near-misses could be perceived as lack of control of an operation. This negative perception will deter the employees of an organization from reporting and tracking information. Therefore, it is paramount that all levels of leadership actively support gathering and reporting this valuable information. Leaders are expected to motivate and train their organizations to be skilled at identifying and reporting PSNMs. Senior manufacturing leadership regularly reinforces this expectation.

In the process safety incident pyramid (Figure 1), a major incident appears at the top with the PSNMs contributing to the base of the pyramid. There are many more PSNMs than major incidents. The ratio of these two should be managed to fit a department’s ability to investigate and learn from the near-misses. The actual ratio for all of Dow in 2015 was around 260:1 — which speaks to how institutionalized the program is. A solid base of the pyramid created by the skills to identify, correct and communicate learnings from a PSNM can effectively reduce the number of major incidents by preventing them before they occur.

In 2012, Dow added a further differentiator to the PSNM program. We strengthened the program by elevating the importance of learnings from the most significant PSNMs. This explicit emphasis on identifying, investigating and corporate leveraging of the events with the highest potential for major impact can only further fortify and drive continuous performance improvement.

We define a high potential (HP) PSNM as an event that, if the circumstances had differed slightly, could have resulted in a fatality, numerous day away from work for staff or substantial community impact. The HP PSNM should provide significant learning value to the corporation or the reinforcement of critical protection layers. The elements of the HP PSNM reporting process include:

• immediately notifying business and technology leaders about an event;

• conducting a formal root cause analysis, with people from process safety and the technology center playing key roles;

• developing an LER by process safety for global distribution across the technologies and sites; and

• positively recognizing the team that identified and reported the HP PSNM.

The additional focus given to HP PSNM events can extend the opportunity to prevent future events beyond the impacted facility or technology in which the near-miss originated. Effectively leveraging the management system opportunities across technologies and sites within a global corporation has a significant impact on eliminating PSIs and protecting the community, personnel, property and the environment.

RCI And Sharing Of Learnings

A root cause investigation determines the underlying reason for a failure. It generally involves people from within the facility, sometimes augmented by corporate experts. An RCI includes documentation of the event, the investigation and learning value. The extent of the investigation (number of team members, cause-effect charting, etc.) should reflect the event’s actual/potential consequences, impact and complexity. All investigations are not created equal. However, every RCI must include these minimum components:

• a root cause analysis;

• determination of the causes for each protection layer failure and associated management system failure;

• recommendation for corrective and preventive actions;

• resolution by emphasizing prevention; and

• documentation of the investigation [7].

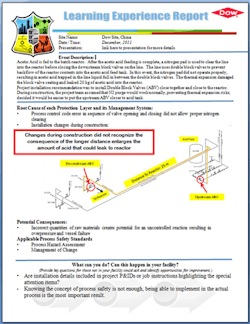

Figure 2. This single page format is simple, direct and broadly applicable.

An RCI can range from informal discussions among two or more people knowledgeable about the incident to more formal techniques like cause-and-effect charting, five whys, failure mode and effects analysis, fishbone diagrams, etc. Effective corrective and preventive actions resolve not only the specific failures but also system and strategy level failures to avert repeat events (or similar events associated with the same management system failures).

Gathering of evidence such as process conditions, sequence of events and operator recollections before the scheduled review is essential. Such evidence enables generating a cause-and-effect diagram to identify the root cause. That diagram must show not only the direct cause(s) such as a failed instrument but also the underlying system cause(s) such as ineffective maintenance for the instrument. This then enables developing corrective actions to address all the identified root causes. The learnings about management system root causes and corrective actions typically are the ones that are most leverageable across a corporation.

With the RCI complete, an LER can be developed. Typically, this report will include the event description, the root causes and corrective actions. The impact of the lessons learned depends on the quality and effectiveness of the communication through which they are shared. We have found that summarizing the key lessons learned from any event into a single page LER containing direct and concise information eases communication beyond the facility that had the incident.

Figure 2 provides an example of an HP PSNM LER. Note that it does not include all of the technical details of what occurred during the event. Rather, the LER’s role is to give enough information to underscore the significant learnings value or the reinforcement of critical protection layers stemming from the event. Restricting the LER to one page provides a format that is simple, direct and easily transferable to a range of disciplines. The key content includes a brief description, root cause(s), consequence(s), what should have prevented the event and, most importantly, key questions to ask of the recipients of the report. For those recipients of wanting full technical details of the event, a link on the LER can point them to a separate document or presentation.

As with any event, the identified root causes are an important lesson. A picture or schematic of key elements of the process related to the event can contribute to an improved understanding of the incident. The LER should include the potential consequences of the event, e.g., chemical release, personnel injury or cost of equipment damaged. It also should highlight the corporate standards or industry best practices that, if effectively in place, could have influenced or prevented the event. Finally, the LER should present challenging questions for readers to ponder. This allows relating the event to their specific situations and so bolsters the opportunity to leverage the lesson learned beyond the boundaries of that single event. One or two questions can generate discussion or serve as a reminder when a similar topic arises.

A Proven Approach

There is no “silver bullet” for reducing PSIs. Strong management systems and constant devotion to process safety at all levels of the organization are necessary to drive that reduction. The programs described in this two-part series were developed and added over many years, some with the hindsight of some serious events that affected people, the environment and company performance. Importantly, Dow leadership has offered unwavering support for our focus on process safety. This focus has been maintained through countless difficult economic times, mergers and acquisitions and numerous other challenges.

Having corporate requirements defined in the process safety and environmental, health and safety (EH&S) strategy systems instead of relying on an accumulation of varying location-specific practices is key to achieving successful performance company-wide. The requirements serve as the framework but it also is essential to have the expertise and focus by all employees on this common goal.

To achieve our goal of zero incidents, we must continue to drive performance improvement by successful implementation of the established systems described in this series. In addition, we must strive to refine those systems and embrace new systems that emerge from innovations as well as learnings from internal and external events. We are not yet at zero — we recognize we have to continue to evolve to get there.

See The Full Paper

This two-part series (read the first article) is based upon portions of a paper given at the 13th Global Congress on Process Safety in San Antonio, Tex., in March 2017. The full paper appears in the Proceedings of the Congress and also will be published in the December 2017 issue of Process Safety Progress.

JOHN CHAMPION is process safety technology leader for The Dow Chemical Co. in Deer Park, Texas. SHEILA VAN GEFFEN is process safety technology leader for Dow in Houston. LYNNETTE BORROUSCH is EH&S director, consumer, infrastructure and industrial solutions, for Dow in Midland, Mich. Email them at [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Klein, J. A., and Vaughen, B. K., “Process Safety: Key Concepts and Practical Approaches,” CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla. (2017).

2. “The U.S. Chemical Safety Board’s Investigation into the Macondo Disaster Finds Offshore Risk Management and Regulatory Oversight Still Inadequate in Gulf of Mexico,” U.S. Chemical Safety Board, Washington, D.C. (Apr. 2016), www.csb.gov/the-us-chemical-safety-boards-investigation-into-the-macondo-disaster-finds-offshore-risk-management-and-regulatory-oversight-still-inadequate-in-gulf-of-mexico/.

3. “Imperial Sugar Company Dust Explosion and Fire,” U.S. Chemical Safety Board, Washington, D.C. (Sept. 2009), www.csb.gov/imperial-sugar-company-dust-explosion-and-fire/.

4. “BP America Refinery Explosion,” U.S. Chemical Safety Board, Washington, D.C. (Mar. 2007), www.csb.gov/bp-america-refinery-explosion/.

5. Van Geffen, S. F., “Are Today’s Engineering Designs Preventing Tomorrow’s Process Safety Incidents?,” presented at the Mary Kay O’Connor Process Safety Center 2013 International Symposium, College Station, Tex. (Oct. 2013).

6. Nesmith, G., Keating, J. T., and Zacharias, L.A., “Investigating Process Safety Near Misses to Improve Performance,” p. 150, Proc. Safety Progr., Vol. 32, Iss. 2 (June 2013).

7. Stevick, K. P., “Next Generation Root Cause Investigation and Analysis — Elimination of Repetitive Incidents through Strengthening Management Systems,” presented at the 11th Global Congress on Process Safety, Austin, Tex. (Apr. 2015).