If you use desiccant air dryers in your plant, you probably know they can consume a lot of energy dollars. Much of this money often is wasted. However, you likely can take a number of steps to reduce your desiccant dryer costs and improve the dryer operation, leading to better air quality. Here, we’ll look at five factors worth attention: specifications check, dryer control, desiccant protection, adjustments and maintenance.

First let’s consider operating costs, though. Compressed air is one of the most expensive utilities to use in doing anything in your plant. This is because of the poor “wire to work” conversion efficiency of the compression process. Only ≈10–15% of the energy put into a compressor actually converts to mechanical energy output at the end user. The percentage is even less if the desiccant dryer consumes some of the air before it gets to the end of the line.

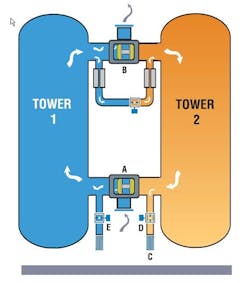

The heatless desiccant dryer (Figure 1) is the most common style of unit in compressed air systems that require dew points at less than 35°F. Such a dryer can be a costly energy hog because it gulps down expensive compressed air just to keep operating. A purge of compressed air must flow in this dryer to reactivate the desiccant once it becomes saturated.

Figure 1. The unit is a fairly complex pneumatic device with a significant number of valves and fittings. Source: Compressed Air Challenge.

A – Inlet valve

B – Outlet valve

C – Exhaust valve and muffler

D – Exhaust valve and muffler

E – Bypass valve to control purge flow

A typical well-maintained heatless dryer using fixed cycle control (i.e., operated via a simple timer) constantly consumes a flow of compressed air of ≈15–20% of the dryer nameplate rating. A 1,000-cfm-rated dryer running fulltime (8,760 h/y) would use roughly 300,000 kWh of energy annually — worth $30,000/y for energy costing $0.10/kWh. If the dryer has standard controls, this cost is constant even if the unit has no plant flow to process. A dryer in poor condition might consume more than rated flow, increasing the costs even more, yet providing poor air quality.

[callToAction ]

Specifications Check

One of the first and most obvious measures to implement to reduce dryer operating costs is to change the style of air dryer. Sometimes a desiccant dryer is installed in a location or on a process that doesn’t need air dried to -40°F levels. This can happen if a plant has a “standard” design practice that is blind to the actual needs of the end use. Consider, for example, a system located indoors in a heated plant. A refrigerated air dryer would consume no compressed air for purge. The refrigerated dryer uses power for its internal cooling circuit but the cost, comparatively speaking, is only a fraction of that of the desiccant dryer when the energy content of the purge flow is considered. A desiccant dryer consumes ≈6–8 times more energy than a refrigerated dryer. A refrigerated dryer that cycles on and off in proportion to moisture loading might use even less power.

One important thing to check is the flow being processed by the air dryer. If an uncontrolled desiccant dryer only is drying, for instance, 10% of its rating, perhaps due to poor sizing choice or design change, because the purge flow remains constant, the dryer will be consuming ≈150–200% of the actual flow being processed, which is extremely inefficient.

So, for lightly loaded dryers, perform a careful engineering analysis of the flows being processed. If you determine the dryer is oversized, then changing the size of the air dryer can greatly reduce the operating costs. Don’t know the flow? Reasonably priced flow meters are available; go buy some.

If you plan to change the dryer but still require a desiccant style, then consider selecting a more-efficient unit that consumes less compressed air for purge. A heated dryer that uses less compressed air or ambient air for desiccant purge or even applies vacuum to remove moisture may cost more to purchase but in the long run can pay for itself in reduced electrical costs.

Dryer Control

You can gain savings by controlling a desiccant dryer using a dew-point-dependent switching strategy. An onboard dew-point sensor will turn off the dryer purge when it’s not required to flow based on the quality of air on the output of the dryer. If the air dryer is processing less than its full load, this strategy will reduce the purge flow roughly in proportion to the percentage dryer loading, purge flow included.

Most modern desiccant dryers can use dew-point control and many have the sensors already installed. If your dryer doesn’t have a sensor, you can retrofit one. Often, plants never have activated installed dew-point controls or have disabled them due to calibration issues. Installation or reactivation of dew-point control on a dryer rated at 1,000 cfm, but loaded at 50%, would save about $15,000 in operating costs per year for an expenditure of about $5,000. As with all sensors, you must not ignore the testing and calibration of dew-point probes; simple calibration errors easily can undermine the most sophisticated dryer control.

Another very common control issue is allowing a desiccant dryer to keep purging when no air at all needs to be processed — for example, a dryer associated with a specific compressor that has been turned off. In such a case, consider controls that will stop the dryer purge when the associated compressor is shut down.

You can use dryer control outputs to help determine if the controls are working properly. Often, the control will track the number of hours the purge savings feature is active. If this information is tracked in a logbook and analyzed by operators, they quickly can detect any change to the normal operation due to sensor failure or other problems.

Desiccant Protection

Even with the best controls, you still diligently must monitor the condition of the desiccant. Contamination of the beads of activated alumina contained in a typical dryer with compressor lubricant or free water will damage or saturate the material, rendering it ineffective to do its primary job.

Every desiccant dryer has a system of filters on the inlet designed to remove contaminant before it gets inside. Of course, as with all filters, you must provide proper care and maintenance or problems will occur. Over time, the filter will become saturated with dirt and scale and will clog, increasing the pressure differential across the dryer and costing extra compressor power. If left unattended, the pressure differential can get so bad the filter will collapse, rendering it useless in protecting the dryer.

In addition, don’t neglect the care of the filter’s associated drains. As the filter collects moisture or lubricant, its collection bowl will fill up; normally some sort of automatic drain expels the liquid. If the drain has failed, then the contaminant eventually will pass through to the dryer. Filters with internal float drains are particularly difficult to troubleshoot because often there’s no obvious way to test the operation. More-modern contaminant drains have easy-to-operate test methods and some sort of visual indication of the liquid level inside the unit so you can confirm proper operation.

On occasion, the inlet filters and, perhaps, moisture separator will be located a fair distance from the dryer. Be aware that if the dryer is processing warm air while it is located in a cold environment, water can condense out of the stream along the section between the filtration and the dryer as the air cools. This can damage or overload the desiccant if allowed to pass through because the dryer isn’t designed to process free water.

You can gain more insights about energy efficiency measures for air dryers by attending one of the Compressed Air Challenge seminars that take place throughout the year. Check out the schedule at www.compressedairchallenge.org.

Adjustments

Often an air dryer will have some sort of valve adjustment of the purge flow. Sometimes this simply is a ball valve that is partially closed to conform to a specified pressure on a purge adjustment gauge. It’s common to find a dryer with an improper adjustment due to unauthorized operation of the valve or failure of the gauge. Purge pressure that is too high will result in excessive flow, adding to operating costs and sometimes overloading the dryer. So, regularly confirm this adjustment is set properly.

If your dryer has fixed orifices that aren’t adjustable, this is less troublesome. However, be aware that the flow of purge will depend on inlet pressure. Occasionally, a plant will place a dryer rated for a lower pressure, say 100 psi, in a system with higher operating pressure, say 125 psi. This will result in a purge flow that’s much higher than required. In such a case, installing the proper sized orifices will make things right. And, if one of your energy efficiency measures is to reduce compressed air operating pressure, don’t forget to readjust your dryer purge flow to the proper level.

Be aware that the desiccant creates dust that can clog outlet filters and, most significantly, the dryer exhaust mufflers. When purging, the dryer tower being regenerated actually is operating at a pressure close to atmospheric, using air that has been expanded to low pressure. This means the flow of air out of the muffler is at fairly high velocity, maximizing the muffler pressure differential. Even a small excess differential across a clogged muffler can greatly reduce the effectiveness of the flow of air in removing moisture from the desiccant. So, change mufflers regularly, replacing them with proper ones rated for the purpose.

Maintenance

A desiccant style dryer is a fairly complex pneumatic device with a significant number of valves and fittings. Over time these items will wear, leak and fail. So, you must provide adequate maintenance and testing of the dryer to keep it operating at peak performance and reduced costs.

One of the most difficult to detect failures in a dryer is leakage between desiccant towers. When this happens, wet air leaks into the side being regenerated, negatively affecting the purge cycle. The consumption of compressed air also will increase, adding to operating costs. Often, the faulty dryer won’t be able to maintain its rated dew point. Rebuilding the dryer valves at regular intervals will help prevent valve failure.

Paying attention to proper application of desiccant air dryers, correct adjustment of their controls, and appropriate maintenance of these devices can go a long way in reducing the associated energy costs.

RON MARSHALL, principal of Marshall Compressed Air Consulting, Winnipeg, MB, is a Compressed Air Challenge instructor. E-mail him at [email protected].