EPA Rolls Out New PFAS Framework

CP editors picked this story as one the top articles for 2023. To view all of our Editors' Choice picks for the year, visit https://chemicalprocessing.com/33016377.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced on June 29, 2023, a new regulatory framework for addressing new per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and new uses of existing PFAS. The framework outlines the EPA’s planned approach when reviewing these chemicals to ensure that, before they are allowed to enter commerce, they meet the safety standard under Section 5 of the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). This article explains the significance of this development.

Under TSCA, the EPA must review new PFAS and new uses of PFAS within 90 days, assess the potential risks to human health and the environment of the chemical and make one of five possible risk determinations. When the EPA identifies potential risks, the agency must take action to mitigate those risks before the chemical can enter commerce.

The EPA recognizes the regulatory challenge to evaluating PFAS “because there is often insufficient information to quantify the risk they may pose and consequently make effective decisions about how to regulate them.” Certain PFAS are known to persist and bioaccumulate in the environment and in people. They pose potential risks to those who directly manufacture, process, distribute, use and dispose of the chemical substances and to the public, including communities that may be exposed to PFAS pollution or waste and already-overburdened communities. The agency will use the framework to assess qualitatively PFAS that are likely persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic (PBT) chemicals.

Framework Elements

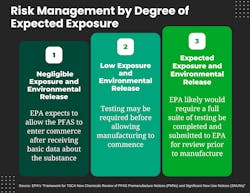

The framework reflects a careful balancing of interests. The EPA expects that some PBT PFAS will not result in exposure and environmental release, such as when PFAS are used in a closed system with occupational protections, as is generally the practice in the manufacture of some semiconductors and other electronic components. In cases of negligible exposure and environmental release, if the EPA can ensure that PBT PFAS can be disposed of properly and no consumer exposure is expected, the agency likely will allow the PFAS or its new use to enter commerce, “after receiving basic information, such as physical/chemical property data, about the substance.”

For PBT PFAS that are expected to have a low but greater than negligible potential for release and environmental exposure, the EPA generally “expects to require test data in addition to physical/chemical properties, such as toxicokinetic data, before allowing manufacturing to commence.” If initial test results cause concern, the agency will require additional testing and risk mitigation before moving forward.

If the EPA determines a PBT PFAS would likely lead to exposure and environmental releases and has no critical use or military need, the EPA states it “generally expects the substance would not be allowed to enter commerce before extensive testing is conducted on physical/chemical properties, toxicity and fate.” For example, according to the EPA, use of PFAS in spray-applied stain guards inherently involves releases to the environment. If the test results cause concern, the agency could require additional testing and risk mitigation before moving forward or could prevent the substance from being manufactured at all.

These policy changes are aligned with the EPA PFAS strategic roadmap and will help prevent unsafe PFAS from entering the environment or harming human health. Data the EPA will obtain on physicochemical properties of any new PBT PFAS and more extensive toxicity and fate data will also support the agency’s efforts under the National PFAS Testing Strategy and advance its understanding of PFAS more broadly.

PFAS Framework Considerations and Implications

The EPA’s new framework is a sensible implementation of its National PFAS Testing Strategy and a reasonable approach to reviewing and regulating new PFAS. The agency will expect robust data, including data on physicochemical properties, fate and toxicity, depending on the conditions of use.

Entities submitting premanufacture notices (PMN) and/or significant new use notices (SNUN) on PFAS should note that the EPA “generally expects that most PFAS will be PBT” and that the framework establishes a de facto ban pending up-front testing if data are not reasonably available. Submitters must be aware of these expectations and develop data prior to submitting a PMN or SNUN. While not all PFAS are PBTs, the burden will be on the submitter to demonstrate the PFAS in question is not a PBT.

The EPA did not provide quantitative cutoffs for determining if the conditions of use for a PBT PFAS represent “negligible exposure and environmental release scenario[s].” Two thoughts come to mind: First, the EPA announced on Aug. 22, 2022, it was discontinuing the use of exposure modeling thresholds when assessing health and environmental risks of new chemicals. The agency established these low-release and exposure (LoREX) thresholds (e.g., incineration air release criterion < 1 µg/m3) based on its “experience gained in conducting risk assessments on over 25,000 new chemical substances. …” The EPA’s interpretation of “negligible” for PBT PFAS is expected to be lower than the LoREX thresholds.

Second, the EPA stated that for PBT PFAS with conditions of use that result in “low exposure and environmental release scenario[s]” (no quantitative cutoffs were provided, but releases and exposures are not zero), it will likely require “both physical/chemical-property testing and other testing (e.g., toxicokinetic testing) be completed and submitted prior to manufacture.” This is an important consideration because the National PFAS Testing Strategy states that testing will likely include additional Tier I testing as well as toxicokinetic testing in rats and mice and possibly a third species. This is noted not as a criticism of the framework, but rather to sensitize potential submitters about the timing and costs of the up-front testing, which will likely take more than two years to complete and cost in excess of $1 million. If the EPA determines it needs to conduct additional testing, the costs and time to complete testing will increase significantly.

A Positive Step, But Questions Remain

Overall, the framework method of gathering additional information on PFAS and its intended regulatory approaches are sensible and balanced. The framework is light on details, however, regarding how it intends to evaluate PFAS and new data on them. It appears the agency will primarily use hazard and fate information as the basis for its determinations. This bears mentioning because the EPA stated that “[r]isk will be qualitatively evaluated due to factors associated with PBT PFAS that represent limitations to the standard New Chemicals Program risk calculation methods, including the known widespread background levels of PFAS present throughout both the environment and humans, as well as the highly persistent and bioaccumulative nature of most well-studied PFAS.”

This is notable because TSCA is a risk-based statute. The EPA should provide clear direction to entities intending to submit PFAS under TSCA Section 5. The agency may lack specific data on novel PFAS chemistries, but it does have the authority under TSCA to require testing to inform and reduce potential uncertainties it may have in its risk assessments. Further, the EPA needs to clarify its testing requirements. As noted, the agency was not transparent on the specific types of data it would mandate as part of its upfront bans, pending testing or on the levels of exposure and/or release that it would consider “negligible” or “low” when making these determinations.

The EPA has raised the bar to commercialize new PFAS and new uses of existing PFAS but has not entirely closed the door. Submitters will need to develop a broad dataset and deploy extensive release and exposure controls to ensure a new PFAS or new use won’t be an unreasonable risk.

About the Author

Lynn L. Bergeson, Compliance Advisor columnist

LYNN L. BERGESON is managing director of Bergeson & Campbell, P.C., a Washington, D.C.-based law firm that concentrates on conventional, biobased, and nanoscale chemical industry issues. She served as chair of the American Bar Association Section of Environment, Energy, and Resources (2005-2006). The views expressed herein are solely those of the author. This column is not intended to provide, nor should be construed as, legal advice.