ShadowBox KO’s Chemical Operator Skills Gaps

Operators often face complex tasks requiring quick, accurate decisions, making cognitive abilities like problem-solving and logical reasoning crucial. Understanding the need to train for effective decision-making, memory retention and adaptability to changing environments, the Center for Operator Performance (COP) has focused on human factors research since it opened its doors in 2007. The COP counts operating companies, including BASF, BP, Chevron, CITGO, Flint Hills Resources and Nova Chemicals, among its members.

To complement its focus, the COP has funded several projects by ShadowBox, a small research and consulting firm focusing on designing cognitive skills training. Joseph Borders, research associate and cognitive psychologist at ShadowBox, has been involved with many of them.

Borders and his ShadowBox colleagues apply a scenario-based training approach that uses cognitive task analysis during client interviews to unearth the expertise — the tacit knowledge — involved in doing a particular job or task. The team works with supervisors or operators at specific plants or units to isolate staff challenges and scenarios.

“A big advantage is that because we’ve worked with different companies — over 10 years with COP members, for example — we can see subtle differences, sometimes cultural, between different companies and even within the same company,” Borders explains. “This can be striking to us as outside observers but not to the companies themselves.”

One of the key issues companies face is event recall, according to Borders. To address this, ShadowBox uses a critical decision-making exercise (DMX), a type of cognitive task analysis that focuses on challenging incidents that individuals have faced in the past.

The exercise uses prompts to help people recall incidents and errors, asking several questions, including: Can you think of a time when you were in (type of incident) and your skills were challenged? Can you think of a time when your skills made a difference — maybe things would have gone differently if you weren’t there?

“We often use this approach, and most of the time, folks can recall one or two such incidents,” says Borders. “But, typically, we are speaking with subject matter experts in the field [who have] a large internal database of incidents they can recall. For folks with less experience, that can be difficult. So, depending on what our goals are for the knowledge capture session, we can use alternative approaches. For example, we sometimes use a tabletop situation for a scenario. Working through that kicks off memories of experiences,” Borders explains.

Another issue is that when operators are doing the same thing every day, they might not see the relevance of a particular event or action. “It’s trying to get them to recall anything out of the ordinary, anything prompting you to think differently in any way, shape or form — those are the things we want to talk about.”

From there, the information has to be captured. One COP member company records the information and uses podcasts to disseminate information.

At another company, a supervisor championed a defunct newsletter containing similar information and brought it back to life. “It’s a really small example, but important. He took the initiative and started reaching out to folks, and that generated interest and momentum. But, again, it took him to do it,” says Borders.

To get a better handle on the current storytelling landscape, Borders and colleagues interviewed training managers and collected 39 survey responses from personnel within COP member companies. “Our goal was to identify gaps and commonalities regarding if and how stories are formally and/or informally used in the industry for knowledge capture and transfer,” he adds.

The report “A Practical Guide to Eliciting, Capturing, and Using Stories to Power Your Organization” was created from that survey. It incorporates a compilation of best practices to identify good stories and describe them with the most impact, elicit stories from a team, extract individual lessons learned — mistakes and successes — and the contrasts between the interpretations of different individuals involved.

Flint Hill Resources, a Wichita, Kansas-based refiner, is using some of the techniques outlined in the report at one of its pilot plants. A formal evaluation of how this is progressing is planned in the near future.

Tell a Story

Another very effective knowledge capture strategy is an anecdote circle, pioneered by Shawn Callahan, founder of storytelling specialists Anecdote International, Melbourne, Australia.

“You ask six to 12 people with experience in the domain or issue you are concerned about to come together in a room, sit in a circle and present a topic of interest. In one case, our topic was troubleshooting and dealing with difficult problems in a unit. All the person has to do is tell a story and share something that happened to them.”

Anecdote circles have some rules: Be honest. Don’t talk over others. Seniority isn’t recognized — everybody is equal on the platform. Also, try not to dominate the conversation. There is a facilitator who is uninvolved but will jump in if any rules are broken.

One two-hour session with a COP member captured over 20 stories, all of which the storytellers were happy to have recorded.

What struck Borders the most during this project was a younger operator with quite a bit less experience than the rest of the group. He hadn’t said anything after nearly two hours, so Borders asked if he wanted to say anything.

According to Borders, the operator said that some of the things people were talking about dealing with 20 to 30 years ago were hard to fathom because efficiency is so much better today. “He was astounded, but he started to appreciate why things are the way they are now and what struck me was him saying I wish everyone on my team could sit in on one of these sessions. The amount of appreciation he got for how things were done and why things are done the way they are now had a large impact on him,” says Borders.

These conversations were used as raw materials to develop scenario-based training stories, too. However, success in storytelling relies on the ability of operators to speak freely without fear of retribution. Blame culture, notes Borders, can be a hurdle.

“Some companies we work with have slogans or mantras about zero tolerance for mistakes or errors. Obviously, nobody wants to make mistakes or errors. But the danger with mantras like these is that when mistakes occur — as they do regularly, on different scales — the likelihood of the people involved sharing what happened with leadership goes way down because no one wants to be the cause of the problem/error.”

The flip side, he says, is that companies with a more resilient culture where people have more candor sharing their incidents and stories learn more from errors.

As an example of the challenge, Borders tells an anecdote about a vice president of a large petrochemical company who was keen to encourage this approach, having previously been very focused on a zero-tolerance philosophy.

While the vice president was meeting with engineers, operators and trainers on-site, he heard that some maintenance staff were using a piece of equipment incorrectly and in a way that could cause injury to themselves and others. So he fired them — at the same time as trying to change the plant’s blame culture.

“One of the things Shawn Callahan talks about is leadership doing remarkable things, inspiring confidence in their company. And the vice president did do a very remarkable thing; just not what he was aiming for.

“So it’s a top-down thing. If the top of the organization shows you are safe — we call it psychological safety — if they can feel safe sharing, then you will get more candor,” Borders added.

What happens next, he says, depends on who the project champion is and who’s funding the project.

The Nova Chemicals Experience

Ron Besuijen, a training specialist with Nova Chemicals, has spent 18 of his 35 years in the petrochemical business, where he trained operations staff. Traditionally, he has used manuals and written procedures to do this.

“However, our processes are often very complex and it’s not possible to write a procedure for every single scenario that might happen. Also, operators sometimes don’t have a lot of time to make choices and decisions, and sometimes one system impacts other systems so it can be very challenging for them,” Besuijen explains.

Hence, the company has been involved with the COP since its formation in 2007, primarily to improve the safety and reliability of its processes.

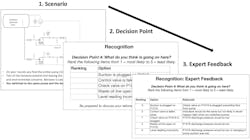

Besuijen’s interest in the organization began with a request to carry out a research project involving the ShadowBox training technique on the company’s high-fidelity dynamic simulator at its Joffre, Alberta, plant (Figure 1).

To prepare, he read Gary Klein’s book “Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions.” Then he looked back at some of the operating decisions he had made in the past and concluded that Klein’s recognition primed decision (RPD) model accurately represented how critical decisions under time constraints are made.

“The key to the RPD model is pattern recognition, and the ShadowBox technique is an excellent tool for developing the required skills to accomplish this. When there are time constraints, we do not always have time to review every possibility analytically, and in fact, the situation could deteriorate if a response is delayed,” he explained.

Besuijen found ShadowBox a good way to share experiences between operators with different levels of experience (Figure 2).

“It built some of the tacit knowledge of experienced operators into our scenarios. The other thing I liked about it is that it steps through the decision-making process, breaking it down into a number of decision points. New operators won’t have developed that concept or skill yet, so practicing using different scenarios in ShadowBox was a really good tool,” he says.

While many of the scenarios are tailored specifically for the ethylene plant at Joffre, others, such as combustion safety, can also be applied to the company’s other two facilities in Ontario and Louisiana.

“Another useful tool developed by ShadowBox and developed through the COP is decision-making exercises (DMX). This is a form of scenario-based training where the operator must determine what the problem is as well as how to fix it. This is typically done in person as a one-on-one discussion,” Besuijen explains.

Although not structured quite like ShadowBox, DMX is still scenario-based. Here, operators are given a graphic or some other form of information and must figure out what happened.

“It could be a failed control valve or transmitter, for example. They must identify this and come up with a way to fix it. That’s what ShadowBox does. It makes them think a little bit more. They also have to look for cues from their indicators to see where the actual problem is. Which is what they have to do in real life,” says Besuijen, adding that the same strategy is used in Nova Chemicals’ troubleshooting courses to develop the skills required there.

Regarding the importance of operator candor in describing their experiences, he defines the culture at Nova Chemicals as pretty good. “I think we’re becoming even more of a learning organization where mistakes and potential mistakes are seen as opportunities to learn rather than to punish.”

To this end, the company is investigating human and organization performance (HOP), a tool that helps safety practitioners look at and do safety differently. Unlike risk management programs that work to eliminate, mitigate or substitute risk, HOP assumes that mistakes will happen. The point is that humans aren’t perfect, and no amount of planning or equipment can change that.

“It’s basically about creating a learning organization where people feel free to share what happened and what they might have done differently if they had seen the situation differently. It’s very easy with hindsight to say, ‘If this person had made a different move at this time, then this wouldn’t have happened.’ But they’re not looking at the whole picture — the other information and distractions that an operator may have had at the time,” he explains.

At the same time, Besuijen points out that initiatives such as ShadowBox must be promoted at a certain level in an organization to be taken seriously.

“There needs to be financial support for it, plus the time needed to develop it properly. It needs commitment from operators and trainers like myself who are willing to document situations so that they get into training systems and are used, too,” he emphasizes.

Following a period of reorganization within Nova Chemicals, Besuijen is now actively encouraging the company’s other units in Ontario and Louisiana to use ShadowBox in a similar way.

About the Author

Seán Ottewell

Editor-at-Large

Seán Crevan Ottewell is Chemical Processing's Editor-at-Large. Seán earned his bachelor's of science degree in biochemistry at the University of Warwick and his master's in radiation biochemistry at the University of London. He served as Science Officer with the UK Department of Environment’s Chernobyl Monitoring Unit’s Food Science Radiation Unit, London. His editorial background includes assistant editor, news editor and then editor of The Chemical Engineer, the Institution of Chemical Engineers’ twice monthly technical journal. Prior to joining Chemical Processing in 2012 he was editor of European Chemical Engineer, European Process Engineer, International Power Engineer, and European Laboratory Scientist, with Setform Limited, London.

He is based in East Mayo, Republic of Ireland, where he and his wife Suzi (a maths, biology and chemistry teacher) host guests from all over the world at their holiday cottage in East Mayo.