The Next Kevlar? Polymer Research Shows Promise

Sixty years after Kevlar was first developed in a DuPont lab, the para-aramid polymer fiber’s heat resistance, high tensile strength and light weight have made it the stock-in-trade for a diverse set of applications.

Possibly best known today for its use in ballistic armor, the polymer now is no stranger to industries including aerospace, automotive, PPE, adhesives and sealants, and emergency response, for example.

However, the 60th birthday celebrations could be overshadowed, at least in part, by two recent developments.

The first is led by a team at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, which has patented a two-dimensional (2D) mechanically interlocked material (MIM) that boasts 100 trillion mechanical bonds/cm2 – the highest ever achieved, they claim.

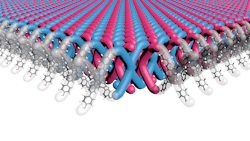

Looking somewhat like good old-fashioned chain mail (Figure 1), the new material is said to exhibit the same qualities of flexibility, strength and light weight that have made Kevlar what it is today.

Another benefit is the polymerization production process, which the inventors of the material describe as highly efficient and scalable.

To reach this stage, however, the team had to overcome some serious drawbacks associated with making polymers from mechanical bonds.

For one, making the initial monomers with mechanical bonds in any but the tiniest amount is challenging. Then, forming mechanical bonds during their polymerization is difficult and inefficient. Thirdly, these limitations really limit how big macromolecules, which use mechanical molecules to hold their extended structure, can be.

Describing their work in a recent issue of Science, the authors note that current methods to achieve this can only make milligram quantities of polymers, and even then they are limited to relatively short chain lengths – 15 is about as good as it gets.

At the same time, they acknowledge that highly efficient methods to form mechanical bonds, especially to produce extended MIMs will impart distinct mechanical, thermal and stimuli-responsive properties and provide access to entirely new polymer architectures.

So, the team turned to topochemical polymerizations, which are known to efficiently link monomers that crystallize with nearby polymerizable groups.

They hypothesized that this crystal engineering concept could be elaborated to form mechanical bonds with unprecedented efficiency.

The polymerization between TPE-PhOH single crystals and SiMe2Cl2 did just this, and the resulting crystals comprise layers and layers of 2D interlocked polymer sheets.

Stronger Composite Materials

William Dichtel, a Robert L. Letsinger professor of chemistry at the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and the study’s corresponding author, said: “It’s similar to chainmail in that it cannot easily rip because each of the mechanical bonds has a bit of freedom to slide around. We are continuing to explore its properties and will probably be studying it for years.”

One property Dichtel has tested is how the new MIM interacts with composites. A 2.5%/97.5% mixture of MIMs/Ultem dramatically increased the Kevlar-related polymer’s strength and toughness.

“We have a lot more analysis to do, but we can tell that it improves the strength of these composite materials,” Dichtel said, adding, “Almost every property we have measured has been exceptional in some way.”

Caltech Researchers: Meet PAM

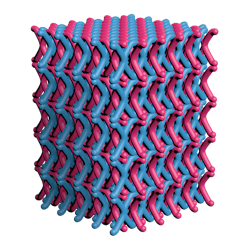

Kevlar’s other putative challenger comes from a new type of matter called polycatenated architected materials (PAMs), developed by researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Pasadena, California.

Architected materials are engineered in a way that the structure of the base elements affects the mechanical properties. In effect, this allows the material to be tuned in response to different stresses; think stimuli-responsible materials, energy absorbing systems and morphing architectures. Helmets and body armor, for example.

In response to small external loads, PAMs behave like non-Newtonian fluids, showing both shear-thinning and shear-thickening responses which can be controlled by their catenation topologies. At larger strains, PAMs behave like lattices and foams, with a nonlinear stress-strain relation. At microscale, PAMs can change their shapes in response to applied electrostatic charges.

Effectively hybrids between granular materials and elastic deformable materials, the individual particles in PAMs are linked as if in crystalline structures, yet free to flow on top of each other and change their relative positions.

A group led by Chiara Daraio, G. Bradford Jones professor of mechanical engineering and applied physics and Heritage Medical Research Institute investigator at Caltech, first modeled their PAMS on a computer, replicating lattice structures found in crystalline substances but with the crystal's fixed particles replaced by entangled rings or cages with multiple sides. These lattices were then printed out into small cubes or spheres using materials such as acrylic polymers, nylon, and metals.

“PAMs are exciting and new,” Daraio said. “We have theories to describe granular matter and theories to describe elastic deformable matter, but nothing that captures these in-between materials. It's a fascinating frontier that promises to redefine what materials are and how they behave.”

About the Author

Seán Ottewell

Editor-at-Large

Seán Crevan Ottewell is Chemical Processing's Editor-at-Large. Seán earned his bachelor's of science degree in biochemistry at the University of Warwick and his master's in radiation biochemistry at the University of London. He served as Science Officer with the UK Department of Environment’s Chernobyl Monitoring Unit’s Food Science Radiation Unit, London. His editorial background includes assistant editor, news editor and then editor of The Chemical Engineer, the Institution of Chemical Engineers’ twice monthly technical journal. Prior to joining Chemical Processing in 2012 he was editor of European Chemical Engineer, European Process Engineer, International Power Engineer, and European Laboratory Scientist, with Setform Limited, London.

He is based in East Mayo, Republic of Ireland, where he and his wife Suzi (a maths, biology and chemistry teacher) host guests from all over the world at their holiday cottage in East Mayo.