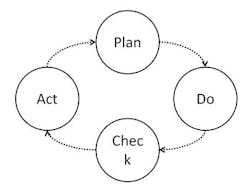

"Operational Excellence" (OE) is a term now in common usage in the business world. But what exactly is OE? Before defining OE, we must put it into context. OE involves efforts at the level of individual processes within an organization. In practice, it demands that any process be designed, executed and improved according to Deming's Plan/Do/Check/Act (PDCA) loop [1] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Following this four-step approach is crucial for progress toward OE.

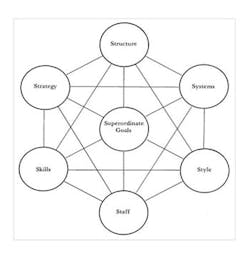

Figure 2. Unless all elements are addressed, improvement efforts will fail.

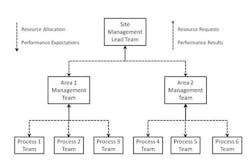

Given that goals are changing and reliability is so important, the second view of OE becomes critical. That is to say, as well as OE representing an end in mind, its never-attainable nature begs for an investigation of "how" it is attained. Having a solid approach to achieving the goals of OE means that reliability can be built into a process and the organization can respond quicker to changing requirements. However, actual performance is the only way to judge the success of efforts. If an organization is using what it considers to be best-in-class approaches to improve OE but defect rates still are very high and not improving, then clearly its approaches are flawed and must change.People execute and manage processes — so, the core of the approach to OE must focus on their behaviors. Such behaviors are the easiest way to see OE when it's being done right (and when it's being done wrong). In addition, we must recognize that behaviors don't just happen but are caused. Therefore, we also must look at the elements that must be in place to promote the right behaviors to support OE and minimize the risk of the wrong behaviors that undermine OE. One way to think about this is to consider how organizations react to human error issues. One approach is simply to consider such errors to be root causes and punish the individuals involved. A more-enlightened approach is to ask why such errors are occurring and whether organizational elements that support people — e.g., training, timeliness of important process data, suppression of nuisance alarms, etc. — are adequate. This view treats improper behaviors as symptoms of gaps in the underlying systems.So, what elements must be in place for OE to be a success? Fortunately, there's an organizing principle that describes the required organizational elements in a useful way. It's called the 7S model.THE 7S MODELThis model (Figure 2) was created in 1980 to show the elements that must be in place for positive organizational change to occur [4]. It defines all elements that must be part of the change and emphasizes that no element on its own is enough.If an organization strives to improve OE but fails to pay attention to all seven elements, it will not succeed. We'll focus on four of the elements — Structure, Strategy, Skills and Systems. We'll look at each as it applies to improving OE across the Do, Check and Act phases, along with some behaviors that may arise if the element isn't addressed.Structure. Effectively implementing OE requires establishing an operations team whose main focus is to run a particular process according to the procedures identified in the Plan phase. Several such process teams report to a higher-level team (e.g., an area management one); all area teams in turn report to a site management lead team (Figure 3). An important aspect of this structure is the relationship between the different levels. Basically, each area team provides performance objectives and resources to its process teams; the process teams then report performance to the area team and request resources from it. (The process teams must have access to functional expertise — quality, safety, engineering and so on — because it would be unreasonable to expect them to have all this expertise.) The area team decides how to allocate resources among process teams based upon needs and opportunities. The same basic relationship exists between the area teams and site lead team. Without a good structure in place to support implementation of OE, prioritization becomes more difficult and process teams may not be sure what are the most important tasks for them to work on. And those priorities may change quickly from day to day as new issues arise. I remember being at a process team meeting once where someone from outside the team was updating it on an issue needing attention. After the person gave the update and left the meeting, the team leader discussed the issue with the team and concluded the team still needed to focus first on the current priority list. In effect, the team leader was providing a firewall if someone later asked why the team wasn't giving this new issue its full and immediate attention.Strategy. A good strategy for OE is to reduce variability in all aspects of our processes and use the reduced variation to accelerate continuous improvement [5,6]. A relentless pursuit of variability reduction is the foundation of the revolution that Deming brought to Japan [7]. Highly variable processes are harder to improve because the variability can hide relationships; it takes longer to see the impact of changes and anticipating their potential unintended consequences is more difficult. Probably the most fundamental behavior seen when OE implementation is low can be expressed by "if it's within specifications, we're okay." This means that variability reduction only is seen as an issue when an output is out of specification. This attitude also arises on the input side where an investigation is being performed after some processing issue. If the inputs, such as raw materials, meet their specifications (as attested by Certificates of Acceptance, for example), then it's assumed they aren't part of the problem. Skills. People need certain skills to implement OE. These fall into three types:1. Skills related to running the process — correctly understanding the work instructions, how to run equipment and so on;2. Skills related to how the process works — adequately comprehending why the work instructions are written the way they are, how the equipment operates (the first principles of the process) and so on; and3. Skills related to process monitoring — properly interpreting the data being produced by the process and responding appropriately.All three types of skills are essential. For example, without the first set of skills, people may interpret the instructions differently, leading to higher variability in the process. Without the second set, people simply assume the current situation is ideal and so may miss opportunities for improving the process. Without the third, people may treat random variation — which occurs in all real processes — as a true change, unnecessarily tampering with a process and actually increasing its variation. (By the way, Deming said success depends upon creating generations of statistically minded engineers and scientists [1].)Systems. Here, we mean the systems that support the process team as it runs the process. Systems can help in at least three ways:1. Increasing efficiency and, hence, easing implementation of OE. For example, computer-based systems can update process data very frequently and store the data for long periods of time — a task not feasible with people-based systems.2. Improving consistency. Embedding key decision algorithms in a system can eliminate variability caused by people. For instance, a system to create control charts for the process can ensure the correct control chart with correctly calculated control limits is used for each type of data being monitored.3. Providing more-sophisticated analysis of the process. There are many different ways to analyze process data. Current developments in "machine learning" (where we train a system to understand what "normal behavior" looks like in a process so it can detect anomalies) are providing very sophisticated approaches that only can be implemented by a computer-based system [8,9].Processes not supported by appropriate systems will exhibit higher variability and less efficiency. So, don't sacrifice OE objectives just to fit within the constraints of an existing system. Instead, design the appropriate system based upon the OE objectives.Figure 3. Implementation requires tiers of teams going down to the individual process.

BERNARD MCGARVEY is a senior engineering advisor for Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Ind. E-mail him at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Deming, W. E., "Out of the Crisis," M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, Mass. (2000).

2. McConnell, J. S., "Analysis and Control of Variation", 4th ed., American Overseas Book Co., Norwood, N.J. (1987)

3. Wheeler, D. J. and Chambers, D. S., "Understanding Statistical Process Control," 2nd ed., SPC Press, Knoxville, Tenn. (1992).

4. Waterman, R. H., Peters, T. J. and Philips, J. R., "Structure is not Organization," Business Horizons, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 14–26 (1980).

5. Wheeler, D. J., "Advanced Topics in Statistical Process Control," SPC Press, Knoxville, Tenn. (1995).

6. McConnell, J. S., Nunnally, B. and McGarvey, B., "Meeting Specifications Is Not Good Enough — The Taguchi Loss Function," J. Validation Technology, Spring 2011.

7. Deming, W.E., "On Some Statistical Aids Toward Economic Production," Interfaces, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 1–15 (1975).

8. Mitchell, T. M., "Machine Learning," McGraw-Hill, New York City (1997).

9. Shmueli, G., Patel, N. R. and Bruce P. C., "Data Mining for Business Intelligence," 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, N.J. (2010).