Does Using Payback Analysis Pay?

Last month, we examined using net present value (NPV) and internal rate of return (IRR) for evaluating project economics (“Properly Assess Economics”). Both NPV and IRR consider the time value of funds. NPV focuses on maximizing wealth generation (quantity) from projects. IRR focuses on maximizing investment efficiency (percentage return) from projects. Other evaluation methods often are used as well. One of the simplest is payback, which is the time a project requires to return the total amount invested.

Payback ignores the time value of money. This seems to run counter to the commonly accepted basis that money has a time value. Many economists insist that a method with discount factors (such as NPV or IRR) always is best. So, should we completely write off payback as a way to select among alternative investments?

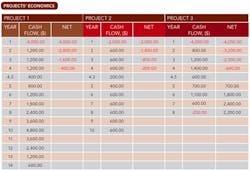

Table 1. The payback periods of Projects 1 and 2 are equal but the long-term returns certainly aren’t.

Consider the three projects whose basic financials appear in Table 1. Both Project 1 and Project 2 have a payback period of 4.3 years. Project 3 has a payback period of 4.5 years but incurs an end-of-life expense that the payback comparison doesn’t include.

An analysis using payback certainly is more straightforward than one using discounted methods. If the earnings are going to be the same every year, the calculation simply involves dividing the expense by the return to determine the payback time. If the expenses or income vary, just add up the yearly amounts until you get a zero balance. Past the zero point, all income is positive.

The logic behind payback analysis is:

• As long as every project returns its investment, then the profits past the payback period are all good.

• The quicker the payback is the better, as that gets you to the profit period sooner.

• Don’t worry about the totals, because so long as you always make good decisions the firm will make a profit.

If all projects had the same life and a smooth cash flow, then few people would criticize using payback analysis for investment decisions. However, different project lives and uneven cash flows make payback analysis less useful. In Table 1, Project 1 and 2 have the same payback period — but Project 1 offers a dramatic profit potential in the later years and will last longer. Project 3 has a different duration and very uneven cash flows. End-of-life outflows (cleanup, demolition and removal) make using payback very questionable.

Despite its limitations, payback analysis does fit some situations.

First, the calculation is very simple to do and the concept is very simple to understand. Never overlook the value of simplicity.

Second, payback is useful when dealing with risk. Political instability, legal uncertainty and rapidly changing markets can push analysis toward short project life and high discount rates. If the discount rate gets high enough, cash flows far in the future have no measurable value. I’ve seen situations where discount rates reflecting unstable situations exceeded 50%. In these circumstances, just using a payback calculation will lead to the same investment decision as more complex methods.

Third, payback often makes sense when self-financing limits projects. If money can’t be borrowed, all project capital must come from retained profits. Most firms have practical limits on how much profit they can hold in reserve for self-financing. The shorter the payback period is the quicker the funds return to retained earnings.

Going back to Table 1, Project 2 may be attractive today but what happens if Project 1 only comes up next year? The quicker Project 2 returns the money, the more able the firm is to jump onto another project. Having reserve amounts returned as soon as possible maintains flexibility to take advantage of even better opportunities.

Specific situations will favor different investment analysis. Balancing investments at any one time may require evaluating some combinations of NPV, IRR and payback. Understand how each fits into finding the best overall allocation of investment.

ANDREW SLOLEY is a Chemical Processing Contributing Editor. You can email him at [email protected].