Welcome back. Well, howd you do on the pop quiz we had last time (CP, June, p. 42)? I hope you did well. Now, well launch into a detailed review of an actual uncertainty analysis.

We have gone through the ins and outs of random, systematic, error, uncertainty, Type A, Type B, ISO, ASME, degrees of freedom, root-sum-square, (bias), (precision), etc. [Ive used parentheses to denote dead terminology, sigh RIP.] Now we need to see how this all works. We need to combine some data via the formulas and technologies weve learned through these many months.

So, lets take a look at some temperature uncertainties and how to handle the expression of the uncertainty in a temperature measurement. Well consider only three sources of uncertainty. This certainly is not typical, as most measurement techniques have dozens of sources of uncertainty. However, three will provide an adequate example.

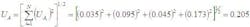

Lets note a few things:

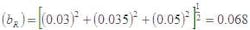

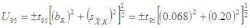

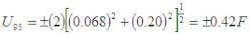

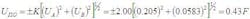

The problem now is which Students t95 to use. For this, we must determine the degrees of freedom for U95. That is done with the dreaded Welch-Satterthwaite approximation. But for now, lets just assume df at least equals 30 and complete the calculation as follows:

In words, the 42F means that 95% of the time the true value for this temperature measurement lies within the interval of the average, 42°F.

Fewer degrees of freedom

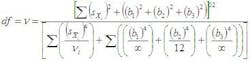

Now well examine what to do if the degrees of freedom dont reach 30. This requires the use of the Welch-Satterthwaite approximation to calculate df (a real pain):

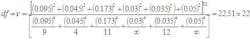

Note that two of the bi terms in the denominator go to zero because weve assumed their degrees of freedom, noted here as , to be infinity. The bi term with only 12 degrees of freedom does not reduce to zero. Putting all the values into this expression gives:

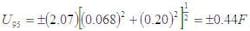

which we round downtruncate to 22 degrees of freedom (to obtain a slightly larger, more conservative uncertainty) and t95 = 2.07. Therefore:

Not much difference is there? Now that wasnt too hard was it?

A soul-searching question

At this point you may well ask: What ever happened to the ISO uncertainty? Lets look into that now.

The engineering/ASME/U.S. model groups uncertainties according to their effect random or systematic in line with the assignments of their original errors.

Random uncertainties are so called because they are estimates of the limits of errors that are random or caused by random effects. Random errors cause observable scatter in repeated test results.

Systematic uncertainties are so called because they are estimates of the limits of errors that arise from systematic causes. The effect of these systematic errors is to displace every measurement from the true value by the same amount for a defined experiment or test. These errors do not cause any observable scatter in test results.

The ISO (International Standards Organization) approach groups uncertainties by their source of information, not their effect on test data. Type A consists of uncertainties whose error sources have data to calculate a standard deviation, while Type B uncertainties are estimated without having data to calculate a standard deviation.

Note that the uncertainty estimates in Table 1 have subscripts A and B. These subscripts define the sources of information from which the uncertainties are estimated. Grouping the uncertainties by Type A and Type B provides an alternative way to calculate the overall, or total, measurement uncertainty. In this case, as with the engineering/ASME/U.S. model, the Welch-Satterthwaite approximation is needed to compute the degrees of freedom for the resulting total uncertainty.

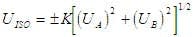

The ISO uncertainty model RSSs elemental uncertainties of Type A and Type B:

where UISO is the measurement uncertainty, UA is the Type A uncertainty for the result, UB is the Type B uncertainty for the result, and K is a multiplier used to obtain the confidence of interest, which often is Students t.

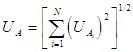

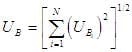

Here, UA and UB are obtained as follows:

and

These are the root-sum-squares of the elemental Type A and Type B uncertainties. Remember, now, Type A uncertainties have data to calculate standard deviations but Type B do not. Often Type B uncertainties are based on engineering judgment.

The degrees of freedom for the are taken from the test data used to calculate the standard deviations. Usually, infinite degrees of freedom are assumed for the . Here, the are estimates of one standard deviation for that uncertainty source.

What answer can we expect for the ISO uncertainty, UISO, at 95% confidence? Try the calculation yourself. You may be surprised.

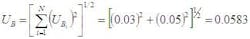

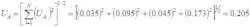

Now look at Table 1 and note that there are four Type A uncertainties and only two Type B. Aha! That makes calculating UB easy:

We then calculate UA:

The ISO uncertainty then becomes:

Here we assumed 30 or more degrees of freedom for the final UISO. Note the subtle use of 2.18 to convert the Type A uncertainty of 0.07 to one effective standard deviation. The 0.07 was in effect a 95% confidence uncertainty that had to be changed to fit into the above equations.

If we dont assume the 30-or-more degrees of freedom, the Welch-Satterthwaite equation given above for the engineering grouping of uncertainties is repeated exactly for the ISO groupings. Not surprisingly, the resulting degrees of freedom and uncertainty match those from the engineering-group calculations. Working the problem to more significant digits is left as an exercise for the reader. (I love that expression!)

See you next time. Until then, remember, use numbers, not adjectives.

Reference:

- Dieck, R. H., Measurement Uncertainty Models, Proceedings of the 42nd International Instrumentation Symposium, San Diego, Calif., ISA, Research Triangle Park, N.C. (1996).

Ron Dieck is principal of Ron Dieck Associates, Inc., Palm Beach Gardens, Fla. E-mail him at [email protected].