Budget reductions often mean that industrial sites must contend with equipment, facilities and infrastructure deteriorating to the point of becoming unusable. While a variety of factors such as poor design, inadequate maintenance, overloading and environmental conditions can contribute to this situation, the culprits almost always include a lack of proper recapitalization.

So, here we’ll look at a method you can use to determine appropriate capital investment.

The key to a good capital investment program is understanding the assets owned and applying basic engineering principles to their evaluation, including condition, performance and expected service life. To do these evaluations, you first must understand recapitalization (or recap). It’s the process of extending the useful life of assets through maintenance/repair and capital investments to keep them in a “qualified state” and “fit for use.” Essentially, it’s part of lifecycle asset management. Note that recapitalization isn’t just for old, obsolete or deteriorating equipment and facilities.

Recapitalization can address:

• Performance. The facility or equipment doesn’t reliably meet the needs of the business or is too expensive to maintain.

• Functionality. Capabilities or functions no longer satisfy current expectations, e.g., in terms of regulatory compliance, efficiency, capacity or technology.

• Productivity. New technology allows for improved economics and provides a positive business case for the capital cost of replacement.

• Industry Trends. Existing equipment falls below current expectations, e.g., for good manufacturing practice (GMP).

To sum up, recapitalization projects are those where assets are either upgraded, replaced or retrofitted due to age, obsolescence or other compelling needs. Projects related to safety/environmental compliance, GMP or administrative upgrades, though new, usually are considered part of recapitalization because they keep the site functional. So is a new building constructed to replace an old one. Recapitalization doesn’t include added assets for production/marketing growth. However, replacement of existing assets, even when it results in some increased output, is considered recapitalization.

Projects that update existing assets mostly for growth or productivity are developed and addressed as part of this process but prioritized separately on the basis of return on investment (ROI) or marketing value. This article doesn’t address these growth and productivity projects.

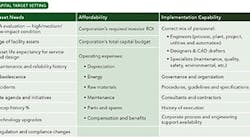

Table 1. A capital budget should reflect an appropriate tradeoff among three factors.

Essential Evaluations

To define and predict the recapitalization, you must continually monitor and analyze the assets’ status. You can accomplish this through computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) data or asset list evaluations.

Assets include facilities, buildings, utilities, infrastructure, automation, information technology/telecommunication and process production equipment.

All sites must perform an annual resource assessment (RA). This involves listing and analyzing key assets. To minimize the effort, the RA only includes those assets of greater value or criticality.

Ultimately, the facility or operations personnel along with maintenance specialists and subject matter experts (SMEs) must evaluate the condition or state of each listed asset based on the four areas of concern: performance, functionality, productivity and industry trends.

The actual asset condition evaluations should consider many factors, including:

1. Reliability — Check the maintenance history of failures, out of tolerance, number of work orders, work-order costs, etc.

2. Age — Compare equipment age to “expected industry standard life” for the asset type, manufacturer and severity of the service, i.e., loading, environment, etc. (We develop an extensive list of typical lifecycles for assets through research with vendors and contractors as well as company history.)

3. Obsolescence — Look at parts or service availability or whether emerging technology or compliance regulations will render the existing asset obsolete.

4. Site initiatives/agenda — Many times, safety, environmental or quality issues will become a site focus and affect the perceived adequacy of an asset.

5. Incidents — Include production lost due to downtime or quality, safety, environmental, audits, findings, etc.

Keep in mind that retrofitting an asset doesn’t mean it will perform optimally for the business needs. For instance, my 1972 Volkswagen was recently overhauled and now is in good shape — but certainly doesn’t match the performance of a new vehicle.

These condition-evaluation techniques ultimately help in the challenging decisions regarding when to upgrade or replace an asset. Waiting too long to recapitalize can pose productivity, quality and compliance risks — but recapitalizing too early ties up funds that could have been spent more appropriately elsewhere.

Categorization

Based on condition evaluations, categorize each asset (larger and critical) as:

• High impact — poor condition (issues need addressing within 0–2 years);

• Medium impact — fair condition (attention required within 3–5 years); or

• Low impact — good condition (efforts can wait for >5 years).

You can put a medium- or low-impact condition with requested funds in the 0–2-year range as long as you indicate it doesn’t require urgent attention in this timeframe but rather deserves consideration if funding is available.

Most sites use a rating system — e.g., high impacts might get a 7–10 on a weighted scale, mediums 4–6, and lows 1–3 — to further delineate the asset’s condition. This helps later in deciding what capital is assigned and what projects get delayed.

Benchmarking with other companies reveals there’s no easy way around development of the asset condition evaluations. Depending on the site size, developing the initial RA database will take 1–3 months but, thereafter, only 1–3 weeks per year to update.

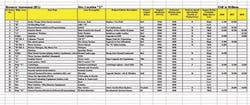

You may wind up with a very large RA summary list. (Figure 1 shows a condensed example.) The process of evaluating the asset condition does take some time initially. However, you then can easily update the completed initial list from year to year as assets are added, revamped, retrofitted, refurbished, upgraded, overhauled or even taken out.

You must include recommended actions, usually retrofits or projects, as well as budgetary estimates by year for each asset with issues. Site management teams then must review and approve the RA list.

You can sort the list in numerous ways (level of impact, type of asset, drivers, recapitalization, growth, productivity, etc.). You can categorize and analyze the assets by individual business units, groups of units, or for the corporation as a whole, as desired. For example, pareto sorts by asset type can reveal where upcoming technical expertise needs are and where procurement can utilize combined buying power. The data and associated metrics obtained can drive continuous improvement through identification of higher performing sites and then sharing of “best practices.” Over years of this continuous improvement, the company’s capital procedures, governance and execution techniques will get better. Metrics to track typically include the following:

1. Percentage of local capital spent on high impact;

2. Percentage of local capital spent on medium impact;

3. Total number of assets evaluated;

4. Total site average asset life;

5. Percentage of total assets evaluated that are high impact;

6. Number of high impacts that made the capital plan;

7. Number of high impacts completed;

8. Percentage of spend not identified on the RA; and

9. Dollar needs for next five years by asset type (cooling towers, roofs, chillers, process tanks, distributed control systems/programmable logic controllers, etc.)

The continuous improvement effort should involve a yearly peer review of the RA on approximately 15–20% of the sites by another engineering group. This review should be performed jointly with the site and other SMEs to ensure proper execution and accuracy while forcing consistency across the corporation. Detection of serious asset condition deterioration or gaps calls for further site visits with more-detailed assessments. Without this, sites interpret execution requirements differently, resulting in issues like asset evaluations missed entirely or improper extreme ratings (e.g., all high- or all low-impact conditions). Ultimately, this creates issues when trying to determine the capital budgets.

Utilizing a technique such as the RA with associated metrics and tracking gives a corporation a tool that produces appropriate data to use in conjunction with other factors for the next step: capital budgeting.

Budget Determination

The actual determination and setting of capital budgets for a site becomes a balancing act between three factors: asset needs, affordability and capability (Table 1).

Asset Needs. As described earlier, knowledgeable personnel from operations, engineering, maintenance and other groups must evaluate the physical state and capability of the facility and equipment assets. This is the main asset factor in setting the capital target (CT). However, other less important characteristics of the “whole site asset portfolio” in general require consideration. These include: age of assets versus life expectancy, maintenance history, asset-related incidents, recapitalization history and change related to compliance, regulations or available technologies. This evaluation should occur on an annual basis, but timing could differ given a site’s unique circumstances. Evaluations result in recommended actions or a capital project investment list.

Of course, at some point each individual project recommendation should undergo a business case evaluation with a risk/benefit discussion because every investment must stand on its own merit.

Occasionally, you’ll find an asset that never seems to get to a replacement state yet that poses increasing risk as it ages. Rating such an item becomes much more difficult; thus, it requires careful monitoring for increased failures or deterioration.

In the end, each asset (and, sometimes, system) must get a high-, medium- or low-impact condition rating. Where needs exist, the appropriate personnel then must estimate the project cost to remedy the situation. Usually, this is a planning or cost opinion estimate only, showing which year(s) the capital need is anticipated.

Affordability. The financial organization within a company usually dictates an overall capital budget based on bottom-line forecasts of profit and return for investors. This takes into account product sales, initiatives and profit projections as well as other internal and external influences. Unless there’s a new product, merger or acquisition, this overall capital budget only changes slightly from year to year. However, engineering can provide input data from the recapitalization evaluation that may influence the total capital budget financial adjustments from year to year.

Business units within a corporation will go through a very similar analysis because they usually are separate profit centers. In addition, specific sites develop their own longer-range strategic plans. From this overall process, the yearly business plans evolve. The details of a business plan will include the operational expenses as a result of capital spent from projects and initiatives including depreciation, energy, maintenance, raw materials, spares/parts and personnel compensation/benefit needs.

Implementation Capability. For capital spend, the best indicator of future performance is past performance. Unless a site changes its organization or processes, performance results from investments will be similar from year to year. Thus, the number of projects and capital spend are a good predictor of the site’s implementation capability. To substantially change that, you must evaluate the agenda and initiatives in terms of both internal and external resources including: internal engineering (process, plant, project, utilities and automation) and specialists (e.g., maintenance, operations, quality, safety, environmental and logistics). Additionally, appropriate SMEs, internal or external consultants, contractors, vendors, etc., must be available.

Always keep in mind that capital plan implementations often fail when workload issues stop a particular engineering group from devoting sufficient time to properly develop, define and help engineer the project details to the level needed for success. These “discipline bottleneck areas” tend to arise where resources sometimes are lacking, e.g., if a particular technology has evolved to the point where it requires more resources than in the past. Inadequate analysis and insufficient level of support put the efficiency and success of a larger capital plan substantially at risk. However, corporations often will give sites with proven performance the flexibility to run larger and larger projects on their own (with some guidance or procedures to follow and report on).

Setting The Budget Target

In theory, the result of the RA, or asset needs evaluation, should drive the capital spend and associated timing for a particular site. However, what usually occurs in practice is that affordability and implementation capability adjust the timing of the remediation projects, thus spreading out the capital spend. Therefore, to reduce the risk of premature failure and to optimize production efficiency, good delineation of project needs is essential. The high/medium/low-impact condition evaluation technique, if done properly, provides this delineation. Corporate finance and engineering need to set CT budgets for the project portfolio for sites. Issues such as capital budget restrictions, a heavy site capital agenda or personnel capacity limitations likely may mandate more-specific delineation — and perhaps revision of the weighted priority scale evaluations.

For each site, we start with the summation of high- and medium-impact condition funds (i.e., critical asset issues requiring addressing within two years and five years, respectively). We take 100% of the high funds needed at a site for the next year being considered to ensure it has the funds necessary for critical items. Then, we add 50% of the medium funds required for the same year being considered, so items less critical, but still of concern, get some money. Failing to provide some funding for a few of the mediums could lead to a flood of capital needs in a few years because many of the mediums could quickly turn into highs.

This approach affords the site some extra funds and flexibility to adjust timing of some items (e.g., due to emergencies, changes in priority or even the desire to address some mediums earlier). This initial funding value provides the baseline for discussion during joint meetings of site, corporate engineering and corporate financial staff. These meetings may lead to adjustments based on the site’s criticality to corporate objectives, site capital plan execution history (or implementation capabilities) and recapitalization versus asset replacement value (ARV) history over time (% of Recap/ARV).

Figure 1. This condensed example shows how key information can be presented.

CT Adjustments

You should adjust the CT as necessary after considering three factors: recapitalization history, corporate objectives’ criticality and site capital execution history.

Recapitalization History. Preventing deterioration requires maintenance, retrofits and upgrades over time. Without these, the deterioration will get to the point where it affects operations, either through equipment failures, facility compromises, quality deviations or even negative effects on employee morale, resulting in further productivity issues. Thus, a site needs the maintenance and recapitalization investments to limit or prevent this.

It’s generally accepted that keeping assets in good shape over time requires the investment each year of a percentage of the site ARV. This percentage varies depending on the industry, type of facility/equipment and age. In fact, the percentage could be as low as 1% or as high as 10% if conditions and situations warrant. Proper evaluation of the trend in asset conditions enables appropriate adjustment of the target percentage. This percentage, sometimes just referred to as the recap rate, is:

ARV Recap % = (“Maintenance & Repair” + Recapitalization)/(ARV × 100)

“Maintenance & Repair” includes all parts, labor, services and contracts, i.e., the asset lifecycle investments into the assets to keep them “fit for use.” You can obtain or develop the site ARV from:

1. Insurance carrier (total insurable asset replacement values excluding raw materials and product);

2. Accounting asset register (original installation values with adjustments for inflation and newly added assets); and

3. Site total installed cost estimate.

Whether using one or a combination of these sources, it’s important to be consistent in developing this value.

Corporate Objectives’ Criticality. If the strategic or budget plans identify a site as crucial to the short- and long-term company objectives, then investment into that site is very important. Thus, at a minimum, you must maintain the targeted recap rate or range. You might even consider raising it for several years to get the site “fit for use,” whatever that may be.

Site Capital Execution History. The ability of a site to implement capital plans effectively in terms of efficiency, spend and schedule largely relates to governance, organizational structure, procedures and resources. In fact, if a site hasn’t historically spent a higher capital value, a large increase without changes to these items may just set the site up for failure.

Adjustments can be a ±% or a lump sum. This depends on senior management site knowledge and discussions.

With all sites’ CT starting points suitably adjusted, compare the total to the allotted capital amount from corporate finance. If it exceeds the available funding, apply a percentage reduction to all sites or make more-specific site adjustments based on the factors previously described. On the other hand, if the CT sum value is less than the funding allotted by corporate, seriously evaluate whether sites have received appropriate amounts or weren’t given enough to fund the critical anticipated needs. To cut sites short in funding is just asking for problems — which usually appear several years later through sharply increased maintenance, reliability issues or failures. This “bathtub” effect shows that the failure risk rate of an asset typically increases dramatically toward the end of its service life. It may be too late to forestall problems at that point.

Recapitalize Realistically

Effective lifecycle management of equipment and facilities is critical to the long-term stability of a corporation. To do this properly requires an investment in resources to develop and maintain a process promoting the monitoring of asset conditions. The process presented here is by no means perfect. In fact, many opportunities exist for further improvements, including: 1) splitting the recap rate into maintenance and capital; 2) further delineating the recap rate/range into site or asset age; and 3) integrating the recap calculation with a site CMMS. With the multitude of factors involved, each company (and site for that matter) will have a different set of parameters to analyze and, ultimately, will develop its own unique philosophy for the recapitalization process. Through continuous improvement, the process will evolve. This will result in improved recapitalization, thus minimizing risks to the corporation’s assets.

Sharing data and methods with other companies often can lead to valuable insights. To participate in a benchmarking effort, contact me.

TERRY LAGRANGE, PE, is the global capital process owner for Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, Ind. Email him at [email protected].